How are China and its signature Belt and Road Initiative perceived in the world? In the West, the prevailing sentiment may be heightened suspicion and distrust, but in developing economies, the picture is markedly different. In a tour d’horizon of various regions, David Arase of the Asia Global Institute examines how the Belt and Road has put China in a more influential and favorable position than its critics would allow.

All aboard the Belt-and-Road express: Celebrating the China-UK rail link in the City of London, 2017 (Credit: Robert Lamb)

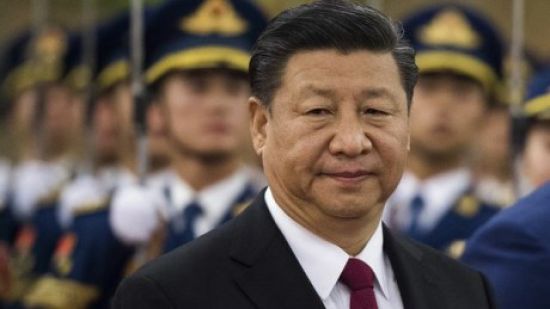

When Xi Jinping unveiled the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road programs of China-financed and -built economic connectivity infrastructure in 2013, the Chinese leader sold it to the world as a public good that would benefit not only those developing countries that signed on as partners in what became known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) but also the entire world by promoting more trade- and foreign investment-driven growth and development to advance globalization further.

Since then, it has been fashionable in the West to criticize China for using the BRI to push onto developing countries excessively large loans to finance inappropriately large infrastructure projects that all too often are socially, environmentally, financially, or technically unsustainable in their local settings. It has not been difficult to identify many high-profile projects across the BRI’s global footprint that arguably illustrate one or more of these shortcomings. But to say that the BRI has been a failure because it has not lived up to the rhetoric that sold it would be the wrong way to evaluate BRI from a realpolitik foreign-policy perspective.

China sold the BRI as a public good, but it always intended the BRI to serve its own national interests and ambitions as a rising great power positioning itself to be dominant in Asia and assume the leading role in global governance by 2049-50 in accordance with Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream” of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. So rather than judge the BRI by whether or not it has always provided affordable, appropriate and well functioning, infrastructure that directly benefits surrounding communities, it is worth looking at how the BRI has supported China’s larger agenda of reshaping regional and global governance where its own interests are actively engaged.

It is often said that China lacks soft power, and what Western audiences tend to hear about it would seem to confirm this. In October 2020, the Pew Research Center published an opinion survey which reported that “unfavorable views of China reach historic highs in many countries” including the US and 11 of its major European and Asian allies and partners.

The BRI does not target the people or governments of these advanced Western nations. Instead, it seeks to attract lower- and middle-income country partners and then influence their beliefs, attitudes and opinions in ways that favor China and its economic, political and security aims. So, to assess China’s soft-power success using BRI, it would be better to look in this direction. Of critical importance are developing Eurasia and contiguous Africa, whose overall support could make the realization of the Chinese Dream a foregone conclusion. When we look here, mostly due to BRI diplomacy and cooperation since 2013, China’s capacity for soft power and prospects for playing a key role in global governance look somewhat better.

Consider these polls. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the 2020 Afrobarometer opinion survey found that 59 percent of Africans believed that top-ranked China’s influence was “somewhat/mostly positive,” edging out the US at 58 percent.

In Europe, strongly negative attitudes toward China prevail due to its abuse of democracy and human rights as well as its disregard for liberal global governance norms. Nevertheless, 18 EU members are Chinese BRI partners, and in Central and Eastern Europe 16 countries (not all are EU members) joined by Greece have attended the BRI-focused 17-Plus-1 annual leaders forum convened by Beijing. In 2020, the Pew Research Center found that in Western European countries, 51 percent of the population see China as the world’s dominant economic power, compared to only 34 percent that see the US in this role.

Thus, the EU faces internal political divisions and conceptual dilemmas as it confronts the conflicting imperatives of an interest-based versus a values-based geostrategic orientation going forward. The heated debate over the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), which was concluded in principle in December 2020, demonstrates the divergence of opinions. In this case, economic interests trumped values as well as a longstanding geopolitical commitment to transatlantic policy coordination.

In Central Asia, a Wilson Center study using public opinion data gathered from 2017-2019 by Central Asia Barometer and the Eurasian Development Bank compared population attitudes toward the US, China and Russia. It found that Russia is most favored by far while “China is in a relatively well regarded second place, and the US comes in decidedly last.”

The situation in South Asia is conflicted. On the one hand, India is hostile to the BRI and China’s presence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region because China is viewed as an outright strategic threat to India’s economic, political and territorial sovereignty. A January 2021 poll by India Today found that 82 percent favored a ban on Chinese imports and mobile phone apps. An August 2020 poll soon after Sino-Indian border clashes in Ladakh that led to the deaths of 20 Indian troops found that 84 percent believed that Xi Jinping had betrayed promises he had made to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Meanwhile, in Sri Lanka to India’s south, the government has maintained its resentment of New Delhi’s role in putting down the Tamil Tiger insurgency. Today, Colombo has become heavily dependent on Beijing and BRI not only due to accumulated past debt but also because China is the only likely source of generous official lending going forward. In February Sri Lanka terminated a joint port development project with India and Japan, signaling a renewed tilt toward China notwithstanding the controversial Hambantota port experience with China.

Thus, in South Asia, India’s neighbors are all tilting toward China, while India in its defiance of Chinese ambition to dominate the region is very much on the defensive. After only seven years of BRI, China has won enough political and strategic influence in South Asia to threaten India’s position as the region’s dominant power.

In Southeast Asia, we have again a situation in which the BRI has propelled Chinese trade and investment to make the fate of many member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) inextricably dependent on China. Beijing is in a position to use these levers to exert its influence across the region, rewarding those aligned with Beijing’s political and strategic interests or punishing those choosing not to cooperate or to challenge China.

Special circumstances make Southeast Asia distinct, however. There is no resident major power that dominates in the region in the way that India does in South Asia. But China has great-power ambitions in the region, posing a threat to the US as the guarantor of prosperity, security and governance norms. While it lacks the military capacity to force this change, it is working to build its capacity to challenge American might. Meanwhile, China has used the BRI to undermine the economic and political influence of the US. And it has wielded gray-zone aggression and hybrid warfare to intimidate US allies and friends. Should there be a big showdown, China hopes that discouraged and traumatized countries will be resigned to align with Beijing and withhold the regional access and support they have traditionally given the US, which allows America to maintain its regional strategic dominance and support maritime governance norms that all but China are willing to support.

On the other hand, China is by far their most important economic partner, and they are compelled by their economic interests to continue deepening economic engagement with China because the US simply cannot offer comparable new trade and investment opportunities. This deepening economic dependence on China pushed forward by the BRI works against their geopolitical freedom to support a US regional presence that defends the current rules-based governance system.

This dilemma explains regional perceptions of China and the US. The 2021 State of Southeast Asia opinion survey published by the Yusof Ishak Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) found that among the elite opinion leaders surveyed in the 10 members of ASEAN, 76.3 percent named China as the most influential economic power in the region, while only 7.4 percent saw the US in this light. Moreover, 48.7 percent saw China as the region’s most influential strategic-political influence; only 30.4 percent gave the US this status.

Nevertheless, 63.1 percent welcomed US strategic influence and 61.5 percent would choose the US, while only 38.5 percent would choose China if they were forced to align with one or the other power. In the South China Sea, 62.4 percent are concerned by China’s militarization and assertive actions. In measuring trust toward major external powers, 63 percent had no confidence in China, putting it in last place, while only 16.5 percent indicated confidence. Japan ranked first in trust, earning the vote of 67.1 percent of respondents, while the US received 48.3 percent to rank third.

Around the world today, 140 countries have signed a bilateral agreement with China to participate in BRI cooperation. As mentioned above, among them are 18 European Union members including Italy, Greece, Portugal and Luxembourg. This collection of BRI partners creates a sizeable grouping for diplomatic and economic cooperation centered on China. This could well be described by the words of Xi Jinping: “a community of shared fate for humankind”. Having used the BRI to gather and consolidate this community under Chinese leadership, China is now expanding the scope of its BRI governance into cultural, political, legal, scientific, technological, and military spheres using associated party-state actors to advance China’s interests across the BRI geostrategic footprint.

BRI may have been sold to the world as a win-win initiative to provide developing countries with infrastructure financing and development opportunities. But Xi will likely measure its success by whether it creates a China-centered “community of shared human fate” and renders to Beijing the ability to reshape regional and global relations to serve China’s great-power ambitions. It would seem that after only seven years, and with many more to go before Xi’s retirement, the BRI has delivered a fair bit of success to China. Now that the fuller meaning of BRI has come into view, the challenge for those wishing to maintain liberal multilateral governance in Asia and the world is to mount an adequate defense against the heretofore successful effort through the BRI to set forth an alternative China-centered global vision.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.