Australia and New Zealand have long viewed the Pacific Islands as part of their sphere of influence. China’s increasing engagement in the region is now throwing that in doubt. Canberra and Wellington must reconfigure their regional strategies to be more inclusive, and recognize Pacific Island states as sovereign actors in their own right.

An April 2018 report that China was in talks to build a military base in Vanuatu highlighted how crowded and complex the geopolitics of the Pacific Islands has become. The report was swiftly denied by Vanuatu’s Foreign Minister Ralph Regenvanu and described as “ridiculous” by the Chinese government.

But, the report generated alarm in Australia, with then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull expressing his “great concern.” That sense of alarm remains palpable in Canberra. Not since the height of World War II has Australia been as focused on the geopolitics of the Pacific Islands. New Zealand’s response was more nuanced, with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern stating that any military arrangement was a matter for the two sovereign nations but that “New Zealand is opposed to the militarization of the Pacific generally.”

The Struggle to Dominate the Pacific Island Sphere of Influence

Australia and New Zealand (and to a lesser extent, the United States and France) have traditionally viewed the Pacific Islands as their sphere of influence. For Australia and New Zealand, the region is of vital strategic import, as it lies across some of their most important sea and air lines of communication. It was consequently the site of major battles fought by these powers during World War II. In the period since, Australia and New Zealand have played a leading role as aid donors in the region. They have also provided substantial defense, policing, and governance assistance, and have intervened in response to regional crises.

Over the past decade, a growing sense of unease has emerged among these traditional powers regarding the increased presence of China, and to a lesser extent, Russia, in the region. In 2011, then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton bluntly declared that "we are in a competition with China” in the region. In June 2018, the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission released a report noting that “China is trying to erode U.S. influence in the region.”

Australia has been more circumspect. For example, Australia’s former foreign minister, Julie Bishop, was quick to water down undiplomatic criticism by Australia’s then-minister for international development and the Pacific, Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, that China’s aid is constructing “useless buildings.” However, like Ardern and her Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Winston Peters, Bishop raised more measured concerns about Chinese development and the implications of debt distress on Pacific Island states.

Not since the height of World War II has Australia been as focused on the geopolitics of the Pacific Islands.

Much attention is focused on China’s aid, because it may enhance its influence in the region to the detriment of the traditional powers. China’s aid to the Pacific Islands has significantly increased, with a recent study finding that between 2011 and 2018, Australia spent A$6.5 billion on the region, while China and New Zealand spent A$1.2 billion each. This generated claims that China will overtake Australia as the largest donor to the region, on the basis that China has committed A$4 billion for the 2017 calendar year, compared to Australia’s A$815 million for the 2017-2018 financial year. However, there is a gap between what China promises and what it spends.

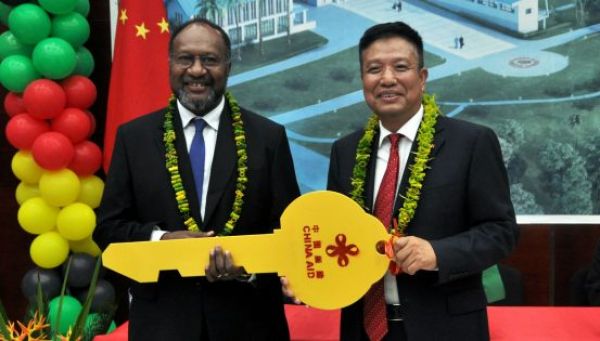

In addition, there are concerns about the types of projects that Chinese aid funds. China’s aid tends to focus on infrastructure. Some of these projects can lead to income generation (for example, improving water supply and roads, or building tuna canneries), but many are unlikely to have significant economic benefits (for example, building sports stadiums).

“Debtbook Diplomacy” and the Currency of Influence

There are also concerns about the nature of China’s aid, 67% of which comes in the form of loans, rather than direct grants. The risk that these loans may create unsustainable debts has been highlighted for several years. In August 2018, Tongan Prime Minister Akilisi Pohiva called on China to write off the region’s debts due to the difficulty Pacific Island states will have servicing them. There are arguments that, should Pacific Island states be unable to service these loans, they may succumb to China’s “debtbook diplomacy” and be forced to give China land or resources, as has occurred in Djibouti, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka. Although, it must be noted that these arguments are treated with skepticism.

These concerns underline that we should not necessarily infer that China’s increased aid will enhance its influence in the Pacific Islands. The fact that all Pacific Island states except Papua New Guinea have decided not to seek more Chinese loans indicates that they are aware of the challenges China’s aid poses. Except for Vanuatu, Pacific Island states have also resisted China’s efforts to coax them into supporting its stance on the South China Sea.

We should not necessarily infer that China’s increased aid will enhance its influence in the Pacific Islands.

However, this does not mean that Australia, New Zealand, and other traditional powers should be complacent regarding the geopolitics of the Pacific Islands. Just as China’s aid does not buy it unmitigated influence in the region, nor does Australia and New Zealand’s aid and other assistance.

This suggests that traditional powers need to rethink their approach to the Pacific Islands. Promisingly, Australia has declared that it is “stepping up” its engagement with the region, while New Zealand has announced an ambitious “reset” of its relations with Pacific Island countries.

The Agency of Pacific Island States

New Zealand’s Pacific reset is purportedly steered by the principles of “understanding,” “friendship,” “mutual benefit,” “collective ambition,” and “sustainability” (although it articulated a more muscular approach in its recent Strategic Defence Policy Statement). Australia’s step-up is focused on “economic growth,” “security,” and “relationships.”

The important distinction between the two is that Australia specifies that security is a driving force in its engagement with the region. This is reflected in Canberra’s attempts to negotiate bilateral security treaties, with one signed with Solomon Islands in August 2017, negotiations underway with Kiribati, and plans to negotiate with Vanuatu. Australia has also signed bilateral security memoranda of agreement with Tuvalu and Nauru.

In addition, Australia is seeking to establish an Australia Pacific Security College to enhance regional security cooperation and has expanded its Pacific Maritime Security Program to assist Pacific Island states to patrol their maritime territories. The college is also seen as a complement to the proposed Biketawa Plus security declaration by members of the Pacific Islands Forum to enhance security cooperation in the region, which Australia and New Zealand support. Draft versions of the Biketawa Plus declaration clearly spell out the need for an expanded concept of security as a consequence of emerging challenges within an evolving and contested security environment.

Pacific Island states are not passive and ripe to be duped by China, Australia, or any other power.

Reflecting concerns about China’s increased presence, Australia has also agreed to spend A$137 million to fund an undersea internet cable between Australia, Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea. Tellingly, Solomon Islands had been in negotiations with Huawei, a Chinese company, to lay the cable. Canberra was said to be concerned about the possibility of Huawei accessing Australia’s telecommunications infrastructure. Papua New Guinea has since outflanked Australia, announcing that Huawei will construct an internet cable within Papua New Guinea, which will then join into the Australian-constructed one.

Papua New Guinea’s decision highlights an oft-overlooked fact in much discussion of the geopolitics of the region: Pacific Island states are not passive and ripe to be duped by China, Australia, or any other power. Instead, they are sovereign states that are acting in assertive and creative ways to pursue their interests.

This suggests that Australia, New Zealand, and other traditional powers that regard the Pacific Islands as their sphere of influence, need to think again. New Zealand will need to ensure that its reset remains guided by its professed principles rather than succumbing to a security imperative. Australia will need to do more than step up its engagement. It needs to follow New Zealand’s lead and articulate a comprehensive “Pacific reset” that respects the sovereignty of Pacific Island states and better seeks to meet both their interests and its own.

Canberra and Wellington’s recalibrated policies toward the Pacific will only be successful and sustainable if they receive buy-in from Pacific Island states and, in an atmosphere of Chinese whispers, the mood is currently one of skepticism.

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.