As Western governments contemplate donating Covid-19 vaccines to other countries particularly developing ones, Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy in the Global South has reinvigorated debate over China’s growing “soft power”. The phrase is loosely used as a catch-all for any number of non-military threats to the Western-led global order. But, write Sophie Zinser of Chatham House and researcher Wendy Wei, such generalizations about China’s nuanced and growing influence detract from real understanding of what brand China is pushing abroad and why. The West desperately needs to understand better Beijing’s foreign policy and its aims.

Public diplomacy in a pandemic: China sends medical supplies to Montenegro (Credit: NATO)

Western analysts have typically regarded Chinese soft power – its ability to influence and persuade using economic and cultural tools – as ineffective, starting as the critics do from China’s authoritarian governance model. While Beijing is estimated to spend more than US$10 billion a year on “soft-power” projects, it is deemed not to be getting its money’s worth. The 2019 Soft Power 30 index, published by political consultancy Portland Communications and the University of Southern California (USC) Center on Public Diplomacy, ranked China 27th out of 30 countries.

Scrutiny in the West of China’s soft power has intensified during the Covid-19 pandemic and with the launch of Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy. Consider these report headlines: “The Ups and Downs of Soft Power in the Asia-Pacific” in The Diplomat, “China Is Losing the Soft-Power War to America” in Bloomberg, and in Foreign Affairs, “Vaccine Diplomacy Is Paying Off for China: Beijing Hasn’t Won the Soft-Power Stakes, but It Has an Early Lead”.

Broad-stroke categorizations in the West of China’s power as either soft or hard, effective or ineffective, demand a closer look. According to Joseph Nye – the Harvard University political scientist who coined the term “soft power” – a country leads the global order by appealing to or attracting other nations through its culture, values and policies rather than its military or coercive “hard power”. The theory goes that when a country achieves legitimate soft-power currency, collective norms emerge that can influence behavior and prompt actions.

While the term “soft power” is used frequently by those in and outside political circles to apply to China and other major powers, it remains too simplistic or vague phrase to describe the nuances of any country’s military, economic, social, cultural and political influence. In a 2011 Chatham House paper, University of Warwick professor Shaun Breslin argued that “simply combining numerous non-military elements together under a single ‘soft’ definition does not allow for nuanced understandings of different typologies and sources of power.” Furthermore, bifurcating policy objectives as either strictly coercive or non-coercive is a practice as impossible as it is useless. This is particularly true of 21st-century policy ambitions such as growing international technological and pharmaceutical influence.

Beyond the extremes of quantitative rankings and sweeping soft-power generalizations, analysts of China need a nuanced understanding of Beijing’s efforts to exert its influence abroad, especially in developing nations. This is particularly important because those very same countries will continue to seek out China as an economic partner.

Further, the new white paper offers fresh commitments to support countries in their “development planning (规划)”, a phrase that echoes China’s own policy-making system of five-year plans. In the 14th Five-Year Plan, unveiled in March, China aims to “promote the global governance system to become more just and reasonable.” The active tone of both statements marks a departure from previous five-year plans and development white papers that emphasized the growth of Chinese economic investments – rather than planning or governance – in the developing world. This is one of the first times that China has stated in a policy document its ambitions for direct engagement with developing-country governments. This is both a mark of confidence in the success of its own model and a sign that its bilateral international diplomatic engagements are set to rise.

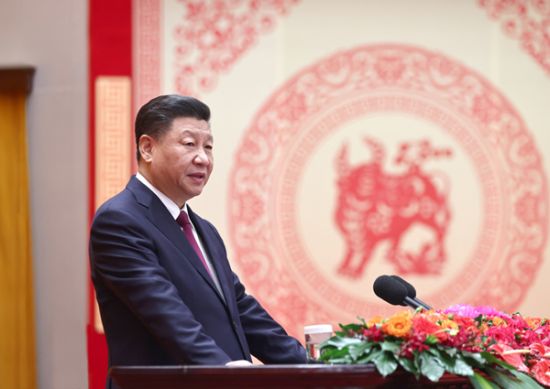

China has certainly spent decades committed to attracting the rest of the world, its leaders referring to the wielding of “soft power”. After Nye coined the term in a 1990 article in Foreign Policy, Chinese leaders and scholars quickly debated the concept and adopted it, expanding on it and applying it to China’s context and practices. In contrast Nye’s sense of soft power as a tool of international diplomacy, at the 17th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2007, Hu Jintao, then the general secretary, linked the idea of “the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” to China’s ability to deploy soft power. Instead of equating China’s influence abroad to its soft power, Hu viewed the Chinese government’s influence on its own people and the nation’s influence abroad as coming from the same source.

The main tool deployed under Hu’s – and now Xi Jinping’s – vision of domestic and global influence is cold, hard cash. According to George Washington University political scientist David Shambaugh, Beijing now spends about US$10 billion a year on state-sponsored image-building programs as part of the Communist Party’s goal essentially to brand market China. Similarly, the scale of the CCP’s Propaganda Department – Zhongxuanbu (中宣部), officially the Publicity Department of the Central Committee – has only grown under Xi. It has funded mostly public-diplomacy programs, which Nye acknowledges as “one aspect of soft power” and in line with China’s state-driven approach.

Another staple of China’s soft-power production is the vast state-run media network boasting numerous bureaux inside China and across the developing world. The well funded image-building strategies rely on the same narrative: China’s undisputedly impressive economic rise. during which hundreds of millions of Chinese people were lifted out of poverty. The messaging continues in the January 2021 white paper, which begins with the sentence: “China is the largest developing country in the world.” And yet paradoxically, China also presents itself in its 14th Five-Year Plan as the only major economy experiencing growth during the Covid-19 pandemic.

China has used this cash-rich image-production strategy rapidly to deploy cultural, educational, and people-to-people exchanges as part of its diplomacy toolbox. Like the United States, China has diversified opportunities for citizens in the developing world to connect with China. A glaring example is the numerous government-funded exchanges with African universities.

Since 2014, it is undeniable that China has been a more attractive destination and partner for nations, especially in commerce, education and tourism. A 2014 Global Attitudes survey conducted by the Pew Research Center was the first to indicate that developing nations’ populations held mostly positive reviews of China. Today, Mandarin-language teaching has been integrated into the public-school systems across Africa as well as Central and Southeast Asia.

The source of China’s soft power is indeed rooted in the economic vitality and promise China wields. African heads of government, for example, have warmly welcomed Beijing’s commitment to non-interference, with no political strings attached to their investment and development assistance. They consider this a more acceptable alternative to US conditioned aid and patronizing preaching.

China’s 14th Five-Year Plan and 2021 white paper describe policies of increasing diplomatic engagement across the country’s existing economic relationships. Top-down public diplomacy asserting China’s economic power will continue to attract critical decision-making sectors in non-democratic states, notably politicians and corporations. But using “soft power” to describe this shift falsely assumes an American trope – that China wants the people of other nations to do and think like its own – which is not backed up by evidence.

The success of China’s influence abroad is instead anchored in how successfully the nation can convince developing states that it is a rich country interested in economic engagement and diplomatic influence through a lead-by-example approach. Unlike what is implied in Nye’s “soft-power” concept, winning hearts and minds on the ground is not necessary for China to exert influence across the developing world. Western analysts do not need to count the number of Confucius Institutes or students studying abroad to see China’s growing global influence. Remaining thoughtful about how and why this trend is occurring instead will make for better Western policymaking on both China and other countries that possess complex economic, social, corporate and political ambitions abroad.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.