China’s presence in the Pacific has taken new forms. What was once purely economic is now much deeper. The expansion of Beijing’s diplomatic outreach and its apparent efforts to build strategic relationships with key Pacific Island nations have prompted the United States and its allies and partners to step up their own engagement with the region, with Washington hosting the first-ever US-Pacific Island Country Summit, write Henryk Szadziewski of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and Graeme Smith of Australian National University.

Fiji bids farewell to US Secretary of State Blinken, February 2022: Beijing’s diplomatic outreach to Pacific Island nations has prompted Washington and its allies and partners to make their own moves (Credit: Pool/Kevin Lamarque)

From small diplomatic measures to a doubling of trade, China’s interests in Pacific Island nations have expanded over the past decade. Now, in a world of growing geopolitical instability and tension over Taiwan, China is in the position of being an enduring partner to the region. Cui Tiankai, who served as China’s ambassador to the US from 2013 to 2021, recently pointed to Australia treating the Pacific as a “backyard”, still holding a view stuck in the past, while China wants a more “modern” relationship with its neighbors.

China’s relationship with the Pacific Islands began with investments in the fisheries and mining sector and has expanded to more comprehensive economic, security and diplomatic ties, particularly following the announcement in 2013 of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Beijing’s signature foreign economic policy program to support infrastructure development in partner countries around the world. Beijing has also expanded its soft diplomacy, offering Pacific Islanders education in areas such as law, agriculture and journalism.

Before the economic ties, however, there were historical ones. People of Chinese heritage have been a presence across the Pacific Islands for over 200 years as traders, speculators, indentured laborers, and political refugees migrated from the south and southeast of China.

Prior to 1975, most Pacific Island countries had recognized Taiwan (as The Republic of China). Fiji and Samoa became the first to develop diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1975. Since then, eight other regional states have switched from Taiwan and developed formal relations with Beijing: Papua New Guinea (1976), Vanuatu (1982), the Federated States of Micronesia (1989), the Cook Islands (1997), Tonga (1998), Niue (2007), the Solomon Islands (2019) and Kiribati (2019).

The Chinese government labels its increasing presence as an expression of “South-South cooperation”: a movement that prioritizes the transfer of knowledge, resources and technology among countries in the Global South. Chinese officials often accuse Western countries of condescension towards Pacific Islanders.

The step up of state engagement began in Fiji in 2006, at the first China-Pacific Island Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Leaders Forum. That gathering of senior politicians set a tone for economic cooperation through grants, loans and preferential trade. “Visit diplomacy” has been a key indicator of increasing Chinese state interest in the region. Since 2014, there have been 32 face-to-face meetings between the Pacific heads of government and Chinese leader Xi Jinping – an unprecedented level of contact compared to Xi’s predecessors Jiang Zemin (1993–2003) and Hu Jintao (2003–2013).

The 2014 meeting in Nadi, Fiji, between Xi and political leaders from eight Pacific Island countries was a notable event in Beijing’s expansion of its outreach efforts. Xi welcomed his counterparts to “take a ride on the Chinese ‘express train’ of development” under the BRI’s Maritime Silk Road. All of Beijing’s regional diplomatic partners have since signed BRI memoranda of understanding. Foreign direct investment rose by 175 percent in the two years after the visit, with 70 percent of the US$2.8 billion invested directed to Papua New Guinea (PNG) alone.

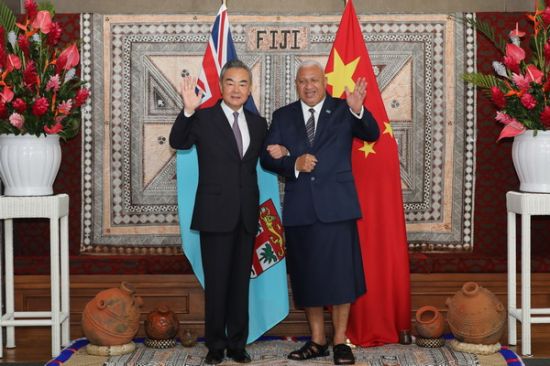

Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi’s tour of seven Pacific Island states in May 2022 was the latest instance of visit diplomacy. It demonstrated how China’s presence has moved beyond economic ties alone. The media across the region described Wang’s eight-nation grand tour as “unprecedented”, but in 2006, his predecessor Li Zhaoxing had visited all eight countries in the Pacific that recognized China at the time. These included three that Wang overlooked – the Federated States of Micronesia, the Cook Islands and Niue, where Li asked the government there to “refrain from attending conferences or anything to do with the Taiwanese government”.

The constant guiding principle in China’s diplomacy is of course the “One-China principle” – the desire to reduce Taiwan’s global diplomatic space. As China’s presence grows, Taiwan’s representatives were shown the door in the Solomon Islands and Kiribati in 2019, just in time for the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic.

The number of diplomats staffing China’s embassies has not grown appreciably across the Pacific – a quirk in the nomenklatura system means central government positions are capped. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs makes up the numbers by drawing officials from provincial and city governments and universities. Embassies also continue to lack the three currencies of Chinese bureaucracy – ren, cai, wu (personnel, funding and facility) – a situation exacerbated by disruptions caused by the pandemic.

While harder to quantify, the caliber of their representatives has certainly improved; recent ambassadors and economic counsellors (who represent the Ministry of Commerce) have been better at engaging with local communities and the media, unlike their predecessors who were preoccupied with sending good news back to Beijing. These ambassadors’ skills have been in great demand. Xue Bing, former ambassador to PNG, was a recent standout for his role in developing closer relations between the two nations but has since moved on to take up a post elsewhere.

China has also expanded its military and policing footprint in the region, with China’s first defense attachés dispatched to PNG and Fiji in 2020. A Chinese police liaison officer was deployed to Fiji in 2021 to lead attachment programs and enhance cooperation between the two nations. In addition to the much discussed (but not yet public) security pact with the Solomon Islands, China had previously inked policing (2011) and security (2014) deals with Fiji.

But Wang’s visit still triggered a rapid uptick in bilateral deals signed with Pacific Island nations. The titles of these agreements suggest they contain elements of the regional deal, but some details of the contents have not been made public. He secured 52 bilateral economic and security agreements following the visit, consolidating Beijing’s status as a regional partner.

China’s aid to the Pacific is substantial, but according to Australian think-tank the Lowy Institute, it peaked in 2016 in line with an overall decline in aid to the region. This could change dramatically if some aid mega-projects – particularly the Ramu 2 hydropower project or the PNG national road network – come to fruition. Despite the advent of a central aid coordination agency in Beijing (CIDCA), China’s aid to the region remains ad hoc and fragmented.

Between 1950 and 2012, Oceania received approximately US$1.8 billion in Chinese aid. China was the second-largest aid donor after Australia to the Pacific region in the latest available data between 2011 and 2018. Just over two-thirds of aid disbursed was as interest-free or concessional loans and the remainder was in the form of grants. Fiji received roughly a quarter of China’s regional aid, second to PNG, which received 32 percent. There has since been a 15 percent decline in Chinese aid from US$2.9 billion in 2018 to US$2.44 billion in 2019.

The line between China’s aid and investment is getting blurrier in the Pacific and elsewhere. One example is the Kumul Submarine Cable Network, majority funded by US$270 million preferential buyer’s credit from the Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim Bank), channeled to local state-owned enterprise PNG DataCo, a wholesale subsidiary of Kumul Telikom Holdings, with work contracted to Huawei Technologies, the Shenzhen-based technology multinational.

While China’s official aid is in decline, the presence of Chinese companies in the Pacific region is not. Investments by Beijing have been linked to office official visits, using state-owned enterprises as an arm of its foreign policy. In the year when PNG hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in 2018, the number of registered Chinese state-owned enterprises in PNG increased from 21 to 39. While researchers are compiling a reliable dataset of China’s companies, it is already clear Chinese enterprises have come to dominate the construction, energy and mining sectors of many Pacific Island states. There is a near monopoly of the retail sector by Chinese business migrants (largely from Fujian and Guangdong provinces).

From 2000 to 2012, a year before the inception of the BRI, the value of trade between China and its diplomatic Pacific partners increased from $US248 million to $US1.77 billion. The value of bilateral trade with Pacific Islands Forum members (excluding Australia and New Zealand) almost doubled, from US$4.5 billion in 2012 to US$8.6 billion in 2018. The Marshall Islands, PNG and Fiji are China’s top export destinations. Between 2012 and 2018, the number of Chinese tourists to Oceania increased from 55,000 to 225,000.

In the past 10 years, China has added two new diplomatic partners and maintains embassies in eight of the 10 countries it has formal relations with (the Cook Islands and Niue are the exceptions). There are currently six Confucius Institutes across the Pacific, two in Fiji and one in each of the Cook Islands, PNG, Samoa and Vanuatu. Suva, the capital of Fiji, is home to one of the world’s 20 China Cultural Centers – venues built to promote “cooperation and communication … by building a bridge for people around the globe to get acquainted with China”. China has also expanded the availability of scholarships and training for students and journalists in the past 10 years.

The United States, meanwhile, is moving to open an embassy in Honiara. Washington is taking a full-court press to step up its Pacific Island diplomacy. On September 22, on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken was to convene a meeting of Partners in the Blue Pacific (PBP) countries – Australia, Japan, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (with India as an observer) – aimed at better coordinating assistance to the Pacific Island nations. Said Kurt Campbell, the White House Indo-Pacific coordinator: "We've seen in the last several years a more ambitious China that seeks to develop footprints militarily and the like in the Indo-Pacific ... that has caused some anxiety with partners like Australia and New Zealand, even countries in the region as a whole." Days after the PBP gathering, on September 28-29 in Washington, American President Joe Biden was scheduled to host the first-ever US-Pacific Island Country Summit.

Amid this flurry of diplomatic courtship of Pacific Island nations by “traditional” partners such as the US and Australia, which are re-evaluating their regional approaches in an effort to limit China’s presence and power, they do so in a world where Pacific Island nation governments are intent on asserting their agency and can determine their own future in response to emerging geopolitical competition for influence.

This article is an edited combination of two separate articles written by the authors – Henryk Szadziewski of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and Graeme Smith of Australian National University – and published under Creative Commons with 360info.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.