The continents-spanning Belt and Road Initiative may appear to be a leviathan, but a closer look at both it and China’s global quest for resources tells a more nuanced story. Even for the most authoritative of actors, situations don’t always work out as they do on paper.

President Xi Jinping is wholly committed to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). He made this clear in front of a large gathering of world leaders at the 1st BRI Summit in May 2017. Given the ongoing decline of the US as a global leader, is BRI participation now something politicians in the developing world cannot reject?

To understand the potential uncertainties and challenges BRI will bring about, let us take half a step back and look for insights by revisiting the not-so-remote history of China’s overseas projects related to natural resources, particularly water, food, and energy. Though BRI, as a policy idea, is relatively new, the actual implementation of its components will build upon many existing bilateral and multilateral projects led by China in previous decades. Therefore, we can expect a level of continuity in at least three ways.

Vision vs. Actions

First of all, behind the staggering political promises, the actual execution of international economic projects is far from uniform and linear. Beyond the Vision and Actions document jointly published by the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Commerce, there is neither a central document that governs the implementation of BRI nor a designated state-level bureaucratic agency to oversee the processes.

As with BRI, China’s global quest for resources took an approach of “letting 100 flowers blossom.” The central government encouraged various players—state-owned enterprises (SOEs), private businesses, and local governments—to search for their own projects to pursue. These players were driven by diverging goals, but the government was content to stay in the back seat, providing only macro-level policy insurance.

Behind the staggering political promises, the actual execution of international economic projects is far from uniform and linear.

Large Chinese SOEs, backed by lines of credit from policy banks, often run pilot projects for the state. They have to comply with basic global market rules, but as businesses, they are afforded much room to make mistakes. The medium-sized, private Chinese-owned businesses that usually fill the gaps in China’s global economic networks also have to comply with market rules. In contrast to SOEs, though, these businesses must calculate cost and benefit more carefully.

After China’s national food policy shifted away from complete self-reliance in grain output in 2013, the state encouraged agricultural SOEs and large private companies to invest globally. However, different companies pursued different tactics to acquire soybeans, cereals, vegetables, and fish, in adherence to varying global market structural features. The outcomes of these ventures were dependent on the countries with which the companies negotiated, from the dominant US to emerging heavyweights like Brazil.

The way Chinese companies enter and invest in a market is constrained by a host of factors, including existing foreign presence and the needs of said market. From 2008 to 2015, 32 Chinese-invested agricultural projects were approved by the Ethiopian government. All except two of the projects involve small-scale farms with products intended for local, not Chinese, markets. Such farms backed by private Chinese businesses are much smaller in scale than licensed agricultural ventures in Ethiopia invested by American, overseas Ethiopian, Israeli, European, and Saudi Arabian companies.

One would imagine that compared to those of SOEs and private Chinese companies, ventures backed by the central government would experience few problems. However, even on this level, business dealings can be complex and heavily influenced by social forces. Such is the case with several dam projects in northern Myanmar that involve not only state-affiliated Chinese investors but also various local businesses and communities. Fierce social resistance against the construction of the Myitsone Dam has led to the suspension of much of the activity of Chinese hydropower companies in the area.

Accounting for Local Considerations

Second, the outcomes of China-invested projects depend more on policy measures taken by host governments than those by the Chinese state or SOEs. For example, the governments of Brazil and Argentina have passed new national laws to prevent foreign attempts at “land grabbing.” The Indonesian government has used its trade ban several times to counterbalance China’s considerable investment in minerals and natural resources. In 2012, Jakarta announced the nickel ban; and, in January 2014, the raw ore ban. Both trade bans were designed to limit Chinese influence in the local mining sector and to reform domestic economic structures to make Indonesia less dependent on exporting raw materials.

The outcomes of China-invested projects depend more on policy measures taken by host governments than those by the Chinese state or SOEs.

Unlike natural resource projects, which usually take place on remote, fixed, and sparsely populated sites, BRI focuses on cross-regional transportation and infrastructure-building. This involves navigating even more complex socio-political relations. Even if the Chinese government could secure solid political support from top leaders in capitals across the globe, politics at local levels can still affect project implementation. In October 2015, China surprisingly outbid Japan and sealed the deal on the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail project with the Indonesian government. However, two years later, while the Chinese side continues to speak confidently of completing the project on time in 2019, many worry that land clearance along the rail will take much more time and political will than expected. With a national general election on the horizon, Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s government will have to be vigilant in handling land-related controversies along the rail.

For many developing countries along BRI’s routes, the rapid inflow of Chinese investment, if not well handled, can open the door to massive social discontent. This is because most of the BRI projects are channeled through the governmental agencies and economic elites of the host countries, often with insufficient attention paid to local interests and disadvantaged groups.

Geopolitics and BRI

Last but not least, we must consider the impact of broader geopolitics on transnational economic cooperation. Competition in the resource economy is often not a determiner but a result of bilateral strategic partnerships (or a lack thereof) between great powers, due to the close ties between resources, territories, and sovereign rights.

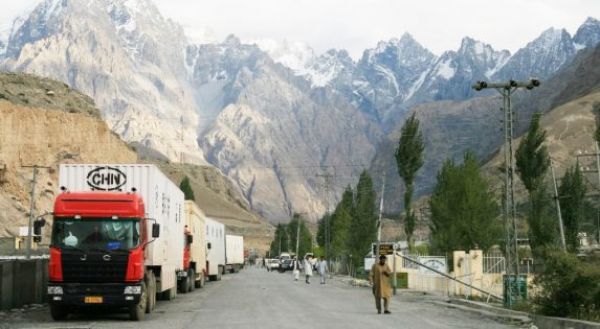

For example, China’s decision to diversify its imports of food products and reduce its dependence on American agricultural exports reflects not only the changing winds of the global market, but also the course of China-US relations. Similarly, energy cooperation between China and Central Asian countries is always affected by China-Russia relations. Even the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project has benefited from the Beijing-Moscow partnership.

Competition in the resource economy is often not a determiner but a result of bilateral strategic partnerships (or a lack thereof) between great powers.

Undoubtedly, some of the BRI projects will be more politicized than China’s resource trading and FDI in previous years. They may also be sensitive to strategic competition between China, the US, and other powers. So far, the US has been cynical, if not dismissive, regarding China’s proposal of a “New Type of Great Power Relations,” the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and BRI. Additionally, among other issues, the two countries are at odds over the South China Sea territorial disputes. In this context, the future of China’s long-term investments in Southeast Asia will encounter more uncertainties beyond normal market risks.

The Balkan region is a relatively new player in China’s global search for economic partnerships. Nevertheless, the significance of this region to BRI is increasing. The “Balkan Silk Road” is China’s gateway to the European market as a whole. So far, the EU has been broadly accepting of China’s investments and projects in the Balkans. However, it is not a complete stretch to imagine a scenario in the future where China gets involved in a direct confrontation with or between the US and Russia over Europe. EU members hosting BRI projects would also be affected if US-China strategic competition escalates.

For the communities on the doorstep of BRI, their most important tasks are to ensure social resilience and to hold local governments and external investors accountable. However, for BRI as a whole, the challenges are multifaceted and, as those for China’s overseas investments in natural resources, lie not only in the nitty-gritty of global markets and production chains, but also in recipient countries’ politics and global power competition, all of which are hardly determined by Beijing alone.

Further Reading

Wu, Fengshi, and Hongzhou Zhang, eds. China's Global Quest for Resources: Energy, Food and Water. London: Routledge, 2017.

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.