In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Japan has gone all in with the US, other Western countries and like-minded nations on applying tough sanctions, essentially abandoning its main diplomatic priority with Moscow. Kato Yoshikazu of the Rakuten Securities Economic Research Institute analyzes the security challenges Tokyo faces, particularly with China, given the possibility that Beijing may attempt to take control of Taiwan.

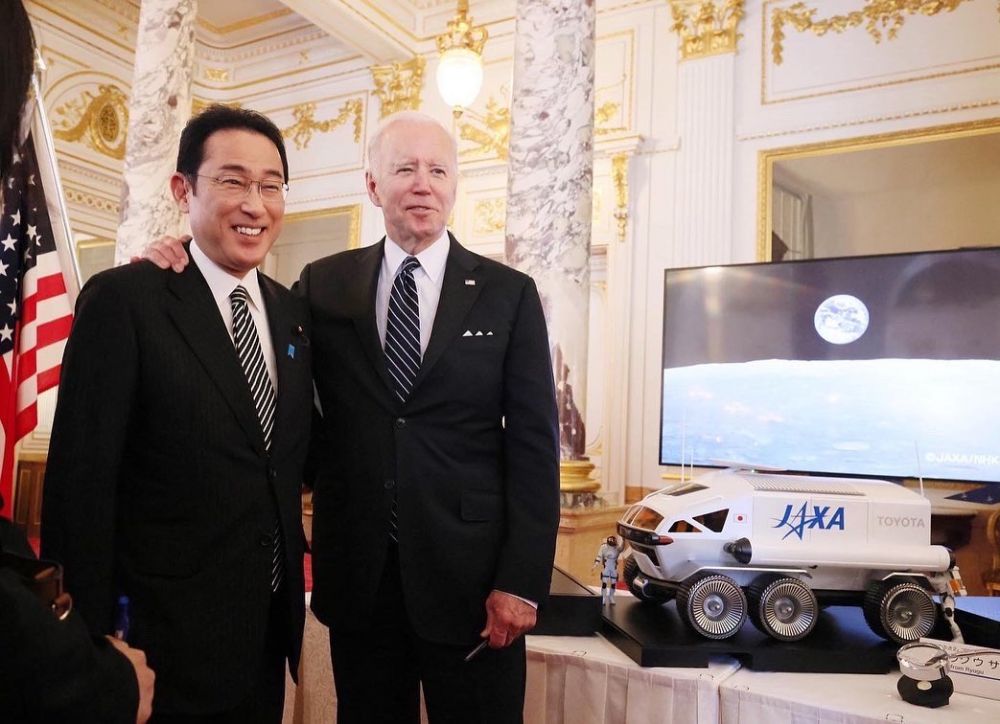

Japanese Prime Minister Kishida and US President Biden in Tokyo, May 23: Washington has your back – and Taiwan's, too (Credit: Prime Minister's Office of Japan)

On February 25, the day after Russia invaded Ukraine, Abe Shinzo, who stepped down as Japanese prime minister in 2020, tweeted: “Russia's invasion of Ukraine is a serious challenge to the international order that we have created since the end of the World War II and must not be allowed. We have to take immediate countermeasures in cooperation with the G7.” During his tenure as Japan’s longest serving head of government (his second term ran from 2012 to 2020), Abe had invested a great deal in his relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin. He visited Russia 11 times, meeting Putin on 27 occasions – not far behind the 38 encounters and counting between Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping. With Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine, Abe’s social-media declaration signaled a shift not just in his attitude towards Moscow and Putin but a wholesale change in Japan’s perspective on its neighbor and the Russian strongman.

Illusion interrupted

Over the decades, one of the clearest goals of Japan’s diplomacy has been to resolve its territorial dispute with Russia over the Northern Territories, four islands off the coast of Hokkaido, and signing a World War II peace treaty with Moscow. Abe had tried hard to achieve this objective which would have been a historic achievement for his administration. “Vladimir, you and I see the same future,” Abe told Putin at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok in September 2019, entreating the Russian leader to settle the longstanding quarrel between the two countries. “Let's run to the finish line together.” Japan has been extending significant economic assistance to Russia as inducements for Moscow’s cooperation.

But since the invasion of Ukraine, all of these efforts have been suspended. Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has been in sync with Abe’s tweet. On March 24, at a G7 summit on Ukraine in Brussels, Kishida conferred with US President Joe Biden before the meeting began, both addressing the other by their first name. “Japan has also shifted its policy towards Russia,” Kishida said. “We would like to strengthen further the Japan-US alliance under the new order.”

The prime minister’s use of the word “shifted” was key. What has actually changed? Over the years, particularly during the Abe administration, though Russia had been criticized and excluded from the G8 due to its annexation of Crimea in 2014, Tokyo’s stance towards Moscow had to some extent differed from Washington’s. Because it had its own diplomatic priority with Russia – the Northern Territories issue and a peace treaty, Japan was always reluctant to join explicit sanctions against Russia. Abe, for example, attended the Eastern Economic Forum hosted by Putin in 2019despite of US opposition.

Now, the Kishida administration has quickly imposed unprecedented sanctions against Russia in full cooperation with other G7 members. The restrictions include financial, trade and visa measures, which the Japanese government has listed in a document, “Japan stands with Ukraine”. In reaction to the policy shift, in late March, the Russian government announced it would halt peace treaty negotiations with Japan, including talks on the Northern Territories issue. “This is extremely unjustified and absolutely unacceptable,” Kishida protested.

But Japan was not surprised by Moscow’s move. In imposing unprecedented sanctions on Russia, in concert with the US and other like-minded nations, Tokyo had essentially abandoned any possibility of making progress towards achieving its chief diplomatic goals. “This is the real shift in Japan’s policy towards Russia – no more strategic ambiguity,” explained a senior diplomat involved in Japan-EU relations at the Japanese ministry of foreign affairs.

Biden and Kishida also expressed their dissatisfaction with China’s attitude on the Russian invasion. They “called on China to stand with the international community and unequivocally condemn Russia’s actions in Ukraine.” The statement also expressed concerns with China over several issues including the South and East China Seas, the recent China-Solomon Islands security agreement, Xinjiang, Hong Kong and most Taiwan. They stated that “their basic positions on Taiwan remain unchanged and reiterated the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait as an indispensable element in security and prosperity in the international community.”

The Biden-Kishida meeting revealed that the Ukraine Crisis has made China factors more complicated for the US-Japan alliance, given the strategic linkage between the Ukrainian war and the Taiwan issue. The reference to China made headline news during Biden’s stay in Japan. At a press conference with Kishida, the US president was asked if he would be willing to get involved militarily to defend Taiwan, he replied with a simple "yes", pausing briefly before adding, "it's a commitment we made." This response drew much attention among the Japanese public and policy community. While Biden had publicly expressed the intention to defend Taiwan at least twice before, this time was different. First, he asserted his position abroad, with the Japanese prime minister standing next to him. And second, this was made in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Although Japan is fully engaged in responding the Ukrainian War, geographically speaking, Taiwan is a much more urgent security matter. Public debate and concern in Japan over what is widely viewed as a crisis have escalated, triggered when in March 2021 Admiral Philip Davidson, then the commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM), told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee in a hearing in Washington that "Taiwan is clearly one of China’s ambitions... And I think the threat is manifest during this decade, in fact, in the next six years.”

With approaching milestones such as the centennial in 2027 of the founding of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and, further off, in 2049, the centenary of the People’s Republic of China, there is much discussion in Japan about not if but when Beijing might make a move on Taiwan, which would be catastrophic for Japan. “A Taiwan emergency is a Japanese emergency,” Abe said in December 2021 on a video link with a think tank in Taipei. “I myself have a strong sense of urgency that ‘Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow’,” Kishida acknowledged in a keynote address to the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on June 10.

Both China and Japan have lessons to learn

Some in the policy circles in Japan argue that China will use force on Taiwan sooner than later. The Russian aggression against Ukraine has complicated the analysis – What might be the lessons for its strategy to unify Taiwan with the mainland that China is deriving from Russia’s actions, its military’s performance and the response of the Ukrainians.

The Japanese policy community is carefully analyzing what conclusions China might draw from the Ukraine war. Meanwhile, Tokyo must consider its position, now that it has is fully on board in applying sanctions on Russia. What does that mean in the context of its engagement with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the transatlantic alliance that is at the forefront of the efforts to support Ukraine. Efforts are already underway to align key Indo-Pacific security players with NATO, which after its summit in June last year took the step of officially calling out “China's stated ambitions and assertive behavior” as “systemic challenges to the rules-based international order and to areas relevant to Alliance security.”

Kishida will attend the NATO summit in Madrid on June 29-30, the first Japanese prime minister to do so. South Korea’s new President Yoon Suk-yeol will also be the first leader of his country to participate. “To be honest, our real purpose of engaging with NATO on the Ukrainian War is for a possible Taiwan crisis,” said the senior Japanese foreign ministry official. “We are leveraging the engagement on Ukraine to seek NATO’s future engagement and support on Taiwan.”

Was Japan right to shift its policy towards Russia, given the costs and the likelihood that its long-sought goal of resolving the Northern Territories issue and signing a peace treaty with Moscow is now unachievable for the foreseeable future? Undoubtedly, the real threat to Japan’s security is neither Russia nor the Ukraine War but China’s assertiveness and possible actions over the Taiwan Strait. There is no dispute over this among the Japanese public and policy community.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the West, liberal democracies and other like-minded nations have become more united. This is a good thing for Japan. Tokyo has no option but to engage fully in this concerted response. The central challenge is how to turn this investment into opportunities to protect Japan’s immediate national security priorities and interests. If China takes military action against Taiwan and the US tries to defend Taiwan militarily, as Biden has said Washington would do, Japan would of course be involved in the conflict. The question is: Can Japan, working with the US and others, possibly even with NATO support, assert the principle of a free and open Indo-Pacific with enough clarity and deterrence to maintain peace and stability in the region?

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.