The US Indo-Pacific strategy, a legacy of the Trump administration, commits Washington to engaging with partners and regional institutions, enhancing economic prosperity, championing good governance, ensuring peace and security and investing in human capital. In his foreign policy, President Joe Biden is likely to focus on the region, particularly China, with the view to shaping a rules-based Indo-Pacific order, what might be regarded as next step after the Obama pivot to Asia. But, as Aristyo Rizka Darmawan of the University of Indonesia observes, any effort to set out economic and strategic frameworks for the vast region will face enormous challenges because of various competing interests, the friction generated by the US-China rivalry, and the abiding importance that states place on asserting national interests over common goals.

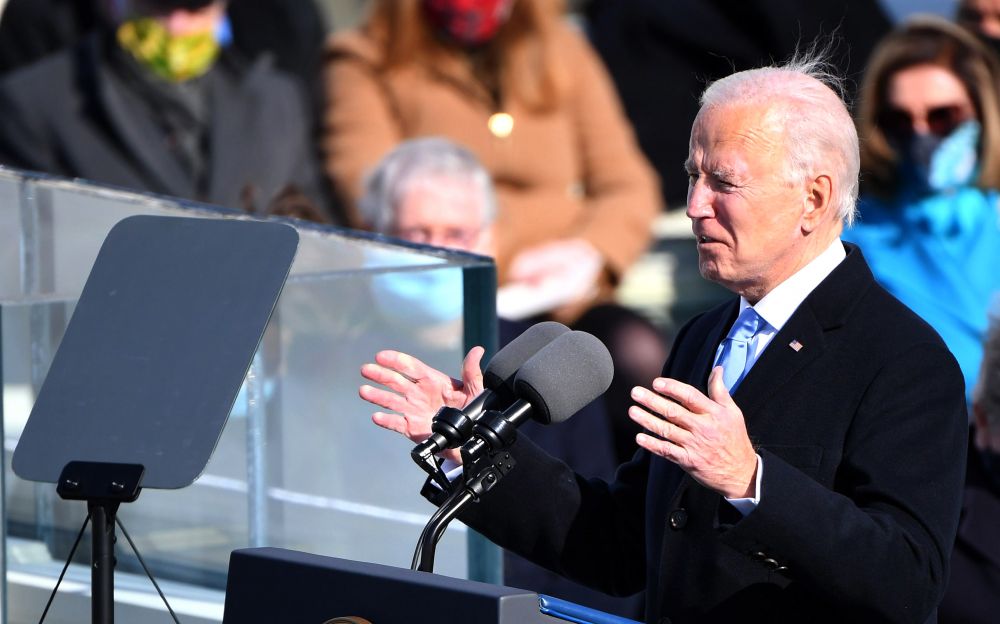

The new US president lays out his challenges: How will Biden adjust his predecessor's Indo-Pacific strategy and approach to China? (Credit: mccv / Shutterstock.com)

Prior to taking office on January 20, US President Joe Biden appointed former Pentagon and State Department official Kurt Campbell as the “Indo-Pacific Coordinator” in the National Security Council. The new president created this position in large part to address concerns arising from China’s ever-growing influence in the Indo-Pacific and to show that the new administration the region will be a key focus of its foreign policy.

In November 2019, the administration of Donald Trump issued a document entitled ”A Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Advancing a Shared Vision”. It underscored that US engagement in the Indo-Pacific would be predicated on the need to counter what Washington viewed as China’s hegemonic ambitions in the region, epitomized by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s ambitious global infrastructure development program. Indeed, the strategy outlined five priorities – engaging partners and regional institutions, enhancing economic prosperity, championing good governance, ensuring peace and security, and investing in human capital – goals meant to highlight accusations that the BRI was marked by poor governance, low-quality projects, the lack of local job creation, debt entrapment, and the fostering of dependency on Beijing.

The US approach dovetailed with Japan’s version of the “free and open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) concept and Tokyo’s Quality Infrastructure Investment (QII) Partnership program, that was framed blatantly to raise questions about the integrity of BRI projects or at least throw shade on China’s intentions for its flagship development-assistance initiative. This left other players in the region struggling to round the sharp edges of these FOIP concepts, which seemed to be much more about containing China and limiting its influence than about supporting economic development and prosperity in the region. India and ASEAN came out with their own interpretations of FOIP, which stressed inclusion and cooperation.

With the arrival of the Biden administration, speculation about how the new president will approach the Indo-Pacific. During the presidential campaign, Biden certainly made clear that he would continue on the Trump tough line with Beijing, though he would use more rational tools than tariffs that American consumers end up paying. He also vowed to shore up relations with allies and partners and work with them to shape a coordinated China strategy. Presumably this would mean that the White House will listen more to leaders in the region, particularly in Seoul, Tokyo and key ASEAN figures.

Asia will be a key focus of Biden’s foreign policy should be no surprise. After all, it was under the presidency of Barack Obama that Campbell and his then-boss Hillary Rodham Clinton launched the “Pivot to Asia”, initially cast as a redeployment of military assets to the region but then made over as a “rebalancing” of diplomacy in consideration for the growing strategic challenges from China as well as Asia’s more important role on the world stage. Obama went so far as to characterize the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal as a tool in this effort – “If we don’t write the rules, China will write the rules out in that region,” he declared in 2015.

Trump, of course, pulled the US out of the TPP, which the eleven other negotiating parties (spearheaded by Japan) took forward, concluding the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which came into effect at the end of 2018. Two years later, 15 countries in the region concluded negotiations for the ASEAN-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), seen as China’s answer to the TPP, though the deal does not match the CPTPP in breadth and quality of commitments to non-tariff reforms.

Who then is writing the rules in the Indo-Pacific? Clearly, that will be a major if not the top concern for the Biden administration, especially in the aftermath of the fracturing of the global rules-based order and the deterioration of multilateralism under Trump.

However, stressing the importance of a rule-based international order in the region and wishing to guide or contribute to its reframing are easier said than done. The Indo-Pacific lacks any coherent regional framework or multilateral governance architecture – a rules-based system that articulates a set of universal norms, values, principles and even laws that aim to maintain peace, prevent conflicts and promote common prosperity in the region. History has shown that upholding international law as a standard of behavior is difficult if not impossible.

In a world that remains firmly Westphalian in its adherence to the traditional concept of sovereignty (despite the emergence of Bretton Woods/United Nations multilateralism after the Second World War, the creation of the European Union, and the adoption 15 years ago of the responsibility to protect as a new norm for international relations), governments tend to focus more on their country’s own national interest in the way that they behave, complying with international law only when it is to their benefit. Consider the disputes over the South China Sea. As American political scientist Ian Hurd of Northwestern University has observed, states have often used international law to justify their foreign policy. It is difficult to measure to what extent international law actually influences state behavior.

Even though it may be difficult to understand the role of international law in world politics, it does not mean that states typically ignore or disobey the rules. As the late Columbia University Law School professor Louis Henkin famously argued, most nations adhere to almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all the time. This occurs because it is usually in the interest of all states to have peace and stability.

ASEAN, which is arguably the only working rules-based framework that, in its various arrangements (from the ASEAN Economic Community to the ASEAN Regional Forum), covers a large part of the Indo-Pacific, was from its inception predicated on the need to secure peace and stability in a world where the greatest geopolitical fear was the spread of communism in a domino effect. ASEAN member states have common strategic interests due to geography, though the concept of “Southeast Asia” may be as artificial a construct as “Asia” itself.

The “Indo-Pacific” is very much an ideal that tries seamlessly to connect the disparate Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean subregions. Indian political scientist Udayan Das of St Xavier’s College in Kolkata maintains that the Indo-Pacific is a product of the growing forces of globalization, trade and changing equations between various actors which has broken down older boundaries and opened up new avenues.

Is a rules-based Indo-Pacific order a possibility? Is it even necessary? If states in the region aim to secure peace and stability in this more volatile, tense world and to bolster regional cooperation especially in such dire circumstances as the ongoing pandemic, then it would seem a worthy goal. The European Union, with its frictions and the calamitous Brexit, may be a cautionary tale about being careful about wishes.

There may be some hope in the area of trade. Put RCEP and the CPTPP side by side and there would seem to be the opportunity for a rules-based Indo-Pacific trade order. But India’s 11th-hour decision to break from the RCEP negotiations, not to mention its own articulation of a FOIP concept, suggests that covering such a vast geographic area is still very much a dream, if not pure fantasy.

The picture is even less promising in the realm of regional security. The Trump administration sought to promote the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or the Quad – Australia, India, Japan and the US – as the seed of a regional security architecture in the vein of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) that would oppose China. But there do not appear to be any takers.

With the diverse interests of the many states and stakeholders in the Indo-Pacific, it will be a huge challenge to uphold any rules-based order in the region. As the pandemic has amply demonstrated, in any pinch, national interests are paramount even if asserting them requires making nice with an adversary or a partner with which a country has an uneasy relationship.

It will be difficult to have a common interpretation of international law. All states may claim that their foreign policy is guided or underpinned by international law but sovereign self-interest reigns. No state will own up to breaching international law. Take China and its appeal to the UN Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to make its case for the nine-dash line in the South China Sea.

There may then be no alternative view than the realist’s – that it will be a major challenge for Indo-Pacific states to identify common interests and agree on a framework for the common respect of international law to prevent conflict. Into this uncertain picture, Biden has entered – in the wake of possibly the most rule-breaking and norm-disrupting US administrations in history. The outlook for peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific looks very challenging indeed.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.