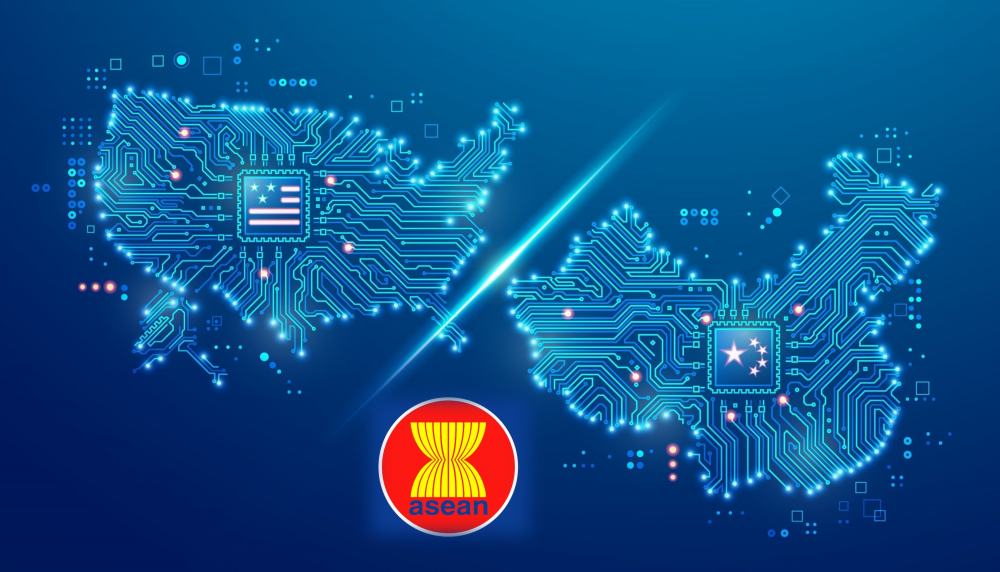

Technology is the major arena for the China-US strategic competition. In this complicated context, Elina Noor of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace looks at the room for maneuver that Southeast Asian economies have as they aim to use technology to fuel their growth and productivity.

Credit: Jackie Niam / Shutterstock.com

The US-China battle for technological supremacy is no longer to be fought in just the complex and distant domains of hypersonics and quantum computing. It is now also a contestation of uninterrupted access to component parts and the capacity to produce them, as well as the ability to move parts and products around. The technology rivalry that pervades the political, military and economic dimensions of Beijing and Washington’s bilateral ties affects networks around the world.

For Southeast Asia, a region invested in both the supply and demand sides of tech, three questions loom large. First, what might the end state of Sino-American competition look like? Second, what does it mean for a Southeast Asia that is counting on technology to fuel growth and productivity gains? And third, where would regional states place themselves if not with either a Washington- or Beijing-led vision?

The American vision for an end-state to competition with China seems to be the preservation of the current global order built upon touted democratic values, with the United States retaining dominance as first among equals. But Washington’s resolve to bury China’s high-tech advances seems more like the existential struggle it foresees rather than a proportionate response to a near-peer competitor. Unilateral export controls are being bolstered by co-opting partners into strangling China’s access to multiple dimensions of semiconductor chip production. This short-term commercial offensive is being paired with longer-term standards-setting economic initiatives such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), reshoring or friend-shoring strategies, and security “minilaterals” including the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) arrangement for nuclear submarine and other advanced technology. Together, they are a multi-pronged response to what the US sees as Beijing’s challenge to “the universal values that have sustained so much of the world’s progress over the past 75 years.”

While China has been forced to be on the defensive, reacting in some ways much like the US, it nevertheless sees itself as offering an alternative model to global governance – one more cooperative, pragmatic and development-focused rather than confrontational. Beijing’s ambitions are undoubtedly sweeping. Domestic blueprints such as A New Generation Artificial Intelligence Plan and Made in China 2025 are complemented by international proposals to reframe the rules of the road. Additionally, China’s state-owned enterprises and private sector have ploughed millions of dollars into satellites, fiber-optic cables, and surveillance cameras. Its Smart City ventures with local host partners abroad now dot Asia, Africa, Latin America and even Europe as part of Beijing’s Digital Silk Road (DSR). The intimation of all these efforts, of course, is a more formidable China taking its rightful place among the world’s established powers. Unsurprisingly, that signaling is one that induces wariness among many countries, large and small.

Irrespective of whether it is China or the United States that emerges triumphant in the race for tech supremacy, whether the battle results in a grinding stalemate, or whether there will be other champions in digital regulation, three things remain true for Southeast Asia.

One, neither Tech Americana nor Tech Sinica is a given. Covid-19 and its still unfolding aftermath underscore how risky it is to assume linear trajectories of history or power. In any event, for Southeast Asia, neither the Chinese nor US model is necessarily desirable. One is not morally or ideologically superior to the other. Despite charges by critics of Beijing’s spread of “techno-authoritarianism” through its use and export of surveillance software and hardware, the United States has had its own disturbing history of surveillance on millions worldwide – even American citizens and the leaders of allied nations – as disclosed by the 2013 leaks by whistleblower Edward Snowden and Freedom of Information Act revelations.

Two, Southeast Asian countries can both capitalize on, and be incapacitated by, the Sino-American tech rivalry. At the manufacturing, assembly, and logistics level, the semiconductor chip wars, prompting shifts in supply chains, and the passage of US legislation such as the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors and Science Act of 2022 (CHIPS Act) present growing opportunities for a majority of Southeast Asian countries.

Malaysia, already a key player in the semiconductor assembly, testing and packaging ecosystem, is looking to expand its back-end capacity to support the anticipated increase in front-end fabrication plants in the United States. The CHIPS Act is also expected to boost US investment in the Philippines, particularly in advanced technology programs, research and development, integrated circuit design, and software development.

Vietnam has drawn additional, large investments from the likes of Apple/Foxconn, Intel and Samsung with Hanoi working hard to position both its location and labor as natural alternatives to China. In 2021, at the height of the pandemic, the Vietnamese government set up a special working group to facilitate and fast-track “high-tech and innovative projects.” Vietnam’s involvement in the semiconductor industry is spread across the value chain spectrum, from chip-design software to manufacturing, assembly, and testing of core processors.

Although not an established player in the semiconductor industry, Indonesia is also hoping to draw some of China’s chip-supply market. Jakarta is courting US investment, pitching Indonesia’s experience in steel production and the availability of raw materials.

Yet, the lure of investment aside, Southeast Asia may also find itself having to unravel or loosen increasingly constricting knots in the regional fabric of connectivity and critical infrastructure involving a range of partners from around Asia (including China), the Pacific, the European Union and the United States. A patchwork of providers diversifies the risk of dependence for third party countries in Southeast Asia. US-China decoupling, however, could complicate platform and infrastructural harmonization or interoperability across the region. The controversy over 5G is illustrative. In particular, the United Kingdom’s 2020 reversal of its earlier decision allowing China’s Huawei Technologies to supply 35 percent of the country’s 5G network following domestic pressure and US sanctions is a cautionary tale for Southeast Asia.

Three, Southeast Asia must set its own course and more proactively contribute to the more consequential arena of contestation: standards-setting. This is where the technical, legal and policy rules of the road governing current and next generation technologies are being (re)set and (re)framed by governments and industry alike to further various agendas. Sometimes, these interests serendipitously align to the common good.

Technical standards-setting in bodies such as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the Third Generation Partner Project is fast becoming another front of competition as China’s drive for standardization in its domestic market makes its way to international fora. The incorporation of these standards into DSR projects around the world as well as China’s participation in United Nations frameworks such as the UN Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security along with the UN Open-Ended Working Group are raising the stakes for governance in the digital tech space. The recent election of Doreen Bogdan-Martin, the American candidate to head the ITU, was not without its geopolitical undertones as she replaced a two-term predecessor from China, Zhao Houlin, and defeated a Russian opponent, Rashid Ismailov.

It is crucial for Southeast Asian countries to contribute actively to unfolding conversations on tech at the international level. All nations large and small but particularly those forming the global majority have a stake in the global digital future. Beyond being mere users or consumers of tech, they are in fact entitled and obligated to help shape the rules of which they are, and will be, a part.

For the majority world, reimagining different models of development and digital pathways to achieving those will be key to autonomy in a future that may otherwise be riven by geopolitical binaries. In other words, third-party countries may ultimately not have to choose between China and the United States especially if they can carve out distinct alternatives that borrow elements from these and other models.

Yet, US-China technological antipathy is not preordained. The comparative advantages of the two are arguably fundamentally different – shockingly, even complementary at times. As unlikely as it seems now, there may come a time when a thaw in bilateral ties could change the course of international tech governance.

Until then, a more equitable future facilitated by tech should not be underpinned by the logic of supremacy, whether in Washington or Beijing, Silicon Valley or Shenzhen, or indeed, anywhere else in the world.

This article is based on discussions by the author at a workshop on “Economic Security and the Future of the Global Order in the Indo-Pacific” hosted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Perry World House on February 22, 2023.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.