In early March, the Chinese government announced purportedly aggressive tax cuts to support the economy. Wei Cui of the University of British Columbia examines major ambiguities in assessing these measures and contrasts the stimulus package with China’s 2020 payroll tax reduction. A key question for China’s policymakers is whether broad business liquidity support and efforts to bolster the labor market will turn out to be necessary.

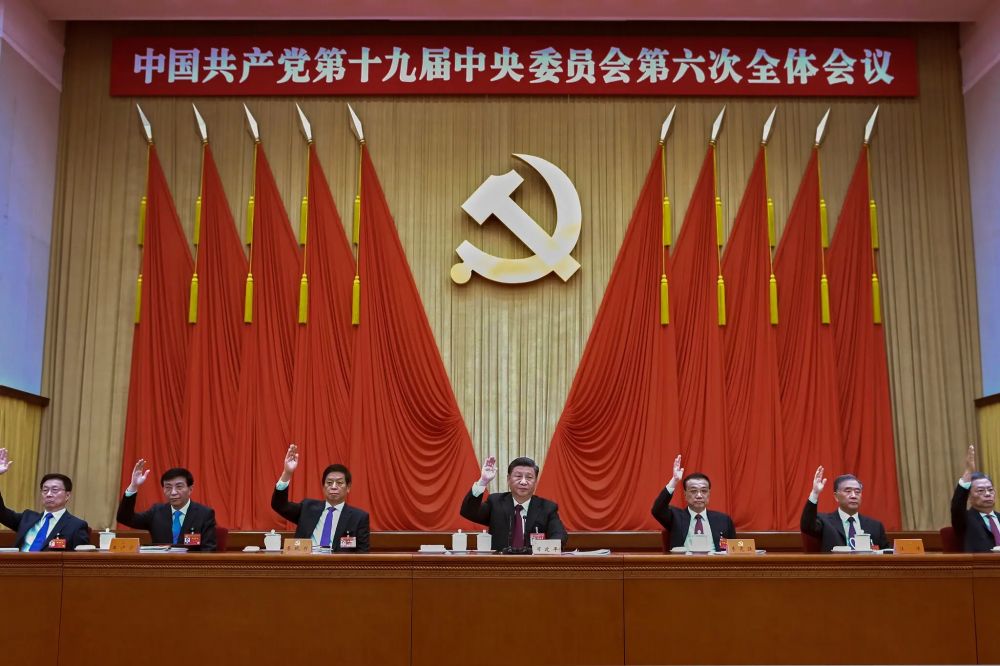

Politburo pledge: China's top leaders have promised to boost its pandemic economic stimulus and meet growth targets imperiled by Covid-19 lockdowns (Credit: Xie Huanchi/Xinhua)

Even before the massive lockdowns in Shanghai and other Chinese cities in April 2022, China’s economy faced strong headwinds, causing the government to lower interest rates in January and announce tax cuts in early March. As the economic disruptions associated with China’s “zero-Covid” policy continue to unfold, the issue of what the government should do to restore quickly-eroding consumer and producer confidence has, for many, taken on even greater urgency. For one thing, how much can tax policy ease the coming economic pains?

To answer that question, it would be useful first to look at the size of the recently announced tax policy stimuli. Yet assessing the size of tax cuts is an exercise fraught with ambiguities. The State Council estimated that the new tax policies introduced in March would result in “tax reductions and refunds” totaling CNY2.5 trillion in 2022. Now, China’s total tax revenue in 2021 was CNY17.27 trillion. A 2.5-trillion-yuan tax cut might seem to suggest that the government is foregoing a remarkable 14.5 percent of its total potential revenue.

Has the government really proposed to shrink itself in such an extraordinary way? Some official media outlets did assert that the government’s goal was precisely to “exceed society’s expectations” in its policy largesse. But how can this be reconciled with the fact that, in the budget tabled at the meeting of the National People’s Congress (NPC) in March, government general revenue is projected to sustain a 3.8 percent increase in 2022?

To address this apparent discrepancy, one could start by noting that 60 percent, or CNY1.5 trillion, of the proposed “tax reductions and refunds” come from one source: refunds of the value added tax (VAT) charged on firms’ input purchases. A key point is that one dollar of input VAT refund does not mean one dollar of foregone revenue. In fact, the benefit to taxpayers is at least one order of magnitude smaller: CNY1.5 trillion of VAT refunds may mean just CNY100 billion in tax savings to taxpayers. That is still a notable amount but not nearly as eye-popping.

The reason for this discrepancy is simple. Buyers pay VAT on purchases and receive VAT invoices from their vendors (who collect and remit the tax collected to the government). For example, a manufacturer purchasing equipment worth CNY1 million is charged 13 percent VAT, pays CNY1.13 million to the equipment vendor, and obtains a VAT invoice for CNY130,000. When the manufacturer makes its own sales, it in turn collects the VAT from customers, but remits only a portion of the VAT collected to the government. If the manufacturer makes sales of CNY1.1 million and collects CNY143,000 of VAT from customers, it will use its CNY130,000 invoice (from the prior equipment purchase) to claim an “input VAT credit”, and remit to the government only CNY13,000. The manufacturer effectively recovers, from its customers, the CNY130,000 of VAT it paid earlier on input purchases.

This is a welcome policy change. Indeed China has been an international outlier in not offering refunds of excess input VAT. But it also explains why a dollar of VAT refund is not equivalent to a dollar of cash benefit to taxpayers. A taxpayer that receives a complete refund today will have no accumulated input VAT to offset the VAT charged on future sales, and therefore will need to remit more VAT in the future. Suppose that, on average, it takes Chinese taxpayers one year to use excess input VAT from one period against VAT on subsequent sales. CNY100 of VAT refund today will therefore mean CNY100 of additional VAT liability next year. If on average firms’ cost of funds is 7 percent a year, the CNY100 of refund gives the taxpayer just CNY7 of economic benefit. Applying this calculation would reduce the real size of the government’s “2.5-trillion-yuan” package by more than half.

Another source of ambiguity for understanding the size of the 2022 tax stimulus is that the Chinese government rarely explains what baselines are used in calculating tax reductions. Consider another new VAT policy. In China, only “regular VAT taxpayers” can claim VAT input credits, yet they represent fewer than 20 percent of VAT-paying business entities and include almost no one from the large population of business sole proprietors. The remaining, “small-scale” VAT taxpayers collect a low turnover tax on sales but cannot claim input VAT credit. They therefore will not benefit from the refund of excess input credits. In 2022, a separate tax benefit is offered to these taxpayers: They are completely exempt from the obligation to collect VAT on sales starting in April, whereas for sales up to March, they need to charge only 1 percent VAT on sales.

The 1 percent rate is a preferential rate first introduced in February 2020 in response to Covid-19 and had been extended till the end of 2021. Before the pandemic, a 3 percent rate applied. Officials reportedly estimate that the 2022 new tax cut for “small-scale” VAT taxpayers will reduce revenue by more than CNY100 billion. But does this estimate assume a baseline rate of 3 percent or 1 percent? If the baseline is a 3 percent rate, then the government is applying a larger tax cut to “small-scale” VAT taxpayers in 2022 than it did in 2020/2021. In these previous years, the rate was cut only to 1 percent, while in 2022 the rate is cut to zero percent for nine months. However, if the baseline used is the 1 percent that already applied in 2020/2021, then the 2022 tax cut is smaller. The rate is reduced from 1 percent to zero, whereas in these earlier years it was reduced from 3 percent to 1 percent.

It is notable that the Ministry of Finance and State Taxation Administration seems more and more to use recent tax holidays as baselines when announcing “newly-added” (xinzeng) tax cuts. This approach leads to smaller estimates of foregone revenue than using the permanent tax rules laid out in the law as baselines. This may appear surprising. One might expect politicians to overstate the generosity of government policies rather than understating it. More important, the approach highlights a real policy predicament: The more tax cuts are enacted now, the more the tax base shrinks and the harder it will be in the future to find room for “new” tax cuts.

Nonetheless, it is possible that China’s tax policy bureaucrats are under real pressure from top political leaders to escalate support for the economy. It may be that President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang want to spare no efforts in ensuring that 2022 is a year of growth and stability. The tax bureaucrats need to convince their superiors, and not just taxpayers, that they have done so.

This can be seen by contrasting the 2022 tax-cut package with the fiscal measures China introduced in 2020. Then, the largest components of China’s fiscal lifeline to the economy were the reductions of and exemptions from employer contributions to various social insurance schemes, i.e. basic pension, health, unemployment, and work-injury insurance. The payroll tax cuts for pension, unemployment, and work-injury insurance were reported to have delivered over CNY1.6 trillion in tax benefits, while those for health insurance reduced government budgets by CNY164.9 billion.

China’s payroll tax cuts in 2020 paralleled and can be compared to wage subsidies introduced in the US, Canada, Australia and other advanced economies in response to the pandemic. All these policies aimed to provide liquidity support to businesses and encourage job retention during Covid-19’s extraordinary shock. In research done at the University of British Columbia, colleagues and I estimated that for Chinese firms that had been making social-insurance contributions, the average value of the 2022 payroll tax cuts covered as much as 67 percent of the predicted cashflow loss caused by Covid-19. Moreover, the cuts likely delivered especially significant benefits to in-person service sectors that were most vulnerable to the pandemic economic shock.

By contrast, while the government’s March 2022 tax-cut package also contains business liquidity support (including the input VAT refunds explained earlier), the size of such support is smaller than in 2020. And at least so far in 2022, support for the labor market has largely been an afterthought. The government seems keener to cut the corporate income tax for already-profitable firms and to encourage them to make fixed-asset investments by enhancing deductions in the computation of firm profits.

Our previous research showed that there are limits to stimuli delivered through the corporate income tax. Too many firms are already loss-making for benefits from lower profit tax rates and additional deductions to be relevant, and too few firms may care to work through tax calculations when making investment decisions. But in 2022, these quibbles may be secondary. The more important question for the Chinese government may be whether continued lockdowns will slow the Chinese economy more than they did in 2020, and whether these adverse developments may again dictate broad liquidity and labor-market supports. If that turns out to be the case, the much-touted size of the March tax cuts may easily be eclipsed.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.