To understand the current and future political development of China and its impact on Chinese external relations such as the strategic rivalry with the US or geopolitical risks in the Asia Pacific including the South China Sea, it is crucial to understand the core of the Chinese Communist Party – Xi Jinping, his character, thinking, intentions and behavior. Yoshikazu Kato of the Asia Global Institute offers an eight-point analysis.

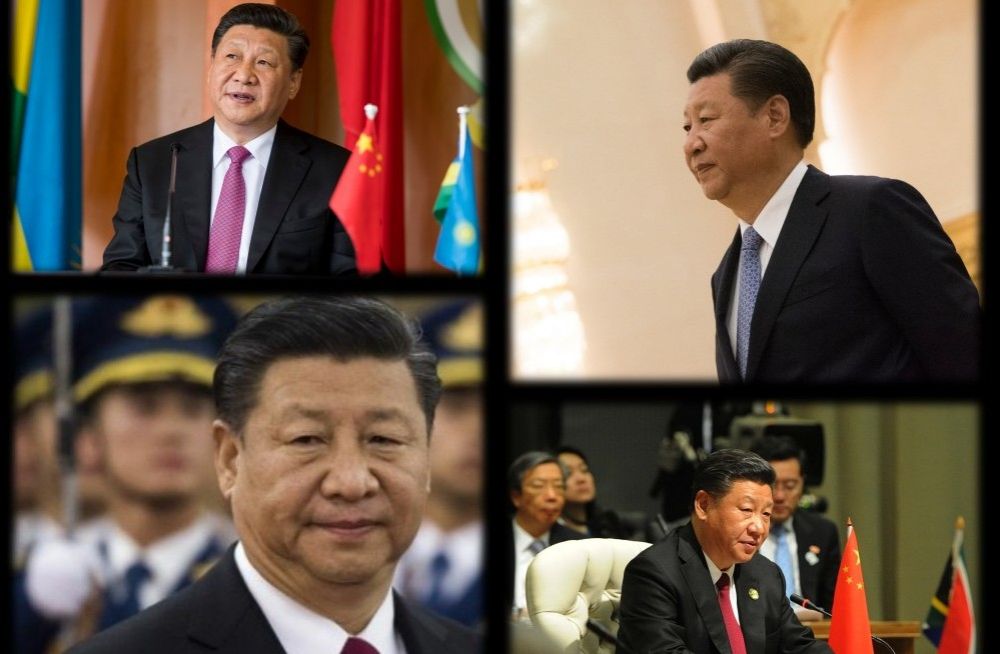

Credits – clockwise, from top left: Government of the Republic of Rwanda, US Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Dominique A Pineiro/US Department of Defense, Siyabulela Duda/Government of the Republic of South Africa, Janne Wittoeck

The arrival of Joe Biden at the White House portends a new chapter in US-China relations. During the administration of Donald Trump, Sino-American ties deteriorated to the point that exchanges between the two countries were reduced to the trading of taunts and barbs over trade, technology, human rights, and regional security. Just weeks before Trump left Washington, his secretary of state Mike Pompeo touched nerves in Beijing by calling China’s actions against Uyghurs “genocide” and loosening limits on interactions with Taiwan, two measures that might remain the US stance under the new president.

Indeed, Pompeo’s replacement, Antony Blinken, has already stated that his predecessor was right in his characterization of the situation with the Uyghurs and expressed support for Taiwan’s self-defense and declared that any attempt by Beijing to use military force against the island would be a “grievous mistake”. The Biden team would continue Trump’s tough posture on China, Blinken stressed, though some of the tools they would use may be different.

Biden himself has long experience engaging China both as a senator for nearly forty years and as Barack Obama’s vice president for eight years. Trump famously boasted about his friendship with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, which he fostered early in his term when he hosted Xi and his wife at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida. Biden comes into office with much deeper knowledge of his counterpart, having spent many hours in private with Xi. He has frequently told the story of a dinner the two shared in 2011 when both were vice president of their countries. Xi asked Biden to define America, to which Biden replied with one word – “possibilities”.

Xi was notably missing from the list of world leaders with whom Biden had phone calls in his first three weeks in office. (The two leaders finally connected on February 11, the eve of the Lunar New Year.) That the American president had spoken to President Vladimir Putin of Russia, also reckoned to be a US adversary, but not yet to Xi suggested that, as the new administration reviews its key relationships, the approach to China will require the utmost care and finesse. Biden has already stated that Washington and Beijing will have to work together on important global challenges such as the pandemic and climate change but that there are many areas where they have profound disagreements (e.g. human rights) and are in stiff competition (e.g. technology).

In late January, the global policy community was buzzing after the publication by the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based think tank, of the paper “The Longer Telegram: Toward A New American China Strategy”, written by an anonymous former senior government official in the same vein as the famous “Long Telegram” on the Soviet Union by American diplomat George Kennan. A key focus of the document is Xi, who “intends to project China’s authoritarian system, coercive foreign policy, and military presence well beyond his country’s own borders to the world at large,” the author contends.

So, who is Xi Jinping?

While many people who have encountered him have spoken about his ambition even in the formative period of his career when he worked for 17 years as an official in Fujian Province, Xi like his predecessors going back to Mao Zedong remains a difficult read.

He is a former Red Guard (老红卫兵), a Tsinghua University engineering graduate, and a so-called “princeling” (太子党), the son of the revolutionary reformer Xi Zhongxun. Xi Jinping served as a governor in relatively developed coastal areas such as Fujian, Zhejiang and Shanghai. His career path as a politician differed from those of Li Keqiang, the current premier, and Hu Chunhua, a vice premier, who are Peking University graduates and former heads of the Communist Youth League.

The biggest feature of Xi’s politics, particularly since he started his second term in 2017, could be defined as “internally repressive and externally assertive”. This is the most straightforward and fundamental reason why the turbulence over Hong Kong, Taiwan, and US-China relations has irreversibly escalated. While the economic rise of China is one factor, none of this could have happened without Xi’s having played a key role in the CCP’s decision-making process and policy orientation.

At a Brookings Institution’s symposium on China in Washington in January 2015, Qin Xiao, a relatively liberal princeling and former chairman of the board of China Merchants Group, named four characteristics of Xi. First, his capabilities – he is far more able at promoting reforms than previous premiers Li Peng or Wen Jiabao. The second attribute was his open mind. “Xi tends to listen seriously to others, including foreigners,” Qin reckoned. The third factor was that Xi in his actions could be more political rather than either technical or bureaucratic. “For example, the decision on China’s accession to the World Trade Organization was political,” according to Qin. The fourth point: “He is a man who can take risks.”

Going beyond Qin’s assessment, here are eight aspects of Xi Jinping that give a sense of his personality and motivations:

1. He is a careful listener

Xi does not make unilateral decisions from his lofty perch in Zhongnanhai. On the contrary, he listens carefully to those whom he trusts, expresses interest in what they think, and takes advice rather than speaking and imposing his own views at occasions such as politburo committee meetings or the CCP’s leading working groups. This does not mean Xi does not have his own perspectives. What is important to note is that Xi needs information and knowledge from comrades to make decisions. In other words, he accepts that on occasions when he has a lack of knowledge and experience of a matter, he must rely on those around him.

In February 2012, when Xi visited Washington as vice president, he met counterpart Biden in the White House. According to an American expert on China familiar with the meeting, Xi asked Biden if he had any advice for him that would make him a better politician. This illustrated how Xi, while he makes his own decisions, is not above consulting and learning from his international peers to acquire useful information to further his political goals.

2. He is the decider

While Xi is willing to listen to others, he eventually makes decisions by himself. In meetings or conferences in the party, according to a fellow princeling who has known Xi for decades, “he does not easily disclose his own opinions; he listens carefully to what colleagues say first, but then makes a decision. Once the decision is made, he will stubbornly stand by it and not allow others to change his mind or intervene.”

These characteristics are reflected in his anti-corruption campaign. Xi kicked out several high-ranking CCP officials such as Zhou Yongkang, Xu Caihou, Ling Jihua, Guo Boxiong and Sun Zhengcai. Given his background as a princeling, removing such important rivals took courage and established Xi as a stubborn and ruthless decision-maker.

3. He breaks rules and norms

Xi has no issue with breaking existing rules and norms. For example, his investigation of former CCP security chief Zhou Yongkang for corruption and abuse of power was unprecedented. Zhou was the only member of the Politburo Standing Committee to be tried and convicted. He was sentenced to life in prison.

On the world stage, he has not shied away from articulating policies and positions that might be regarded as provocative. In 2013, Xi asserted China’s hegemony in the Pacific, saying in a meeting with Obama in California that “the vast Pacific Ocean has enough space for China and the US”. In May 2014, Xi outlined a “New Asian Security Concept” at a conference in Shanghai: “Matters in Asia ultimately must be taken care of by Asians. Asia's problems ultimately must be resolved by Asians. And Asia's security ultimately must be protected by Asians.”

4. He has strong ties to Russia

In March 2013, Xi chose to go to Russia on his first trip abroad as president. According to Chinese reporters, at a meeting in the Kremlin, Xi suddenly told counterpart Putin that “we are somehow similar”. The US and its allies have viewed with concern closer Russia-China relations under Xi and the mutually supportive personal relationship between Xi and Putin. China’s muted response to Russia’s aggression in Crimea and Russia’s similar approach to China’s military expansion in the South China Sea have been regarded in the West as damaging to the liberal rules-based international order and a possible play for regional hegemony in an effort to counter American global leadership.

5. He wants to control everything

Xi has consolidated party and political power counter to Deng’s administrative reforms on separation of powers in 1980s. He has been in charge of many Central Leading Groups (领导小组) and policy coordinating bodies including those concerned with deepening reforms across a wide swathe of areas including national defense and the military, national security, finance and foreign affairs. While these many issues require collective decision-making, including input from retired senior officials and princelings, Xi has taken the lead, bolstered by his own sense of confidence and deep understanding of the challenges. He clearly aspires to control everything rather than share power.

6. He is a risk taker

Xi’s controlling character and his willingness to take risks could be a tricky combination. The CCP could well make policy misjudgments, particularly on important matters such as relations with the US, Taiwan, management of the economy, the military, and political and social controls.

By being a risk taker, Xi himself might be considered a source of risk. Consider his assertive policies including a more robust foreign policy particularly towards the US, tough stances on Hong Kong and Taiwan, repressive actions to rein in political freedom and social activism, and the aggressive anti-corruption campaign have created enemies and prompted pushback, which might potentially undermine Xi’s political position, cut into his power and possibly negatively affect the CCP’s legitimacy and standing.

7. He is unpredictable

Xi’s unprecedented anti-corruption campaign, the abolition of the presidential term limit, and the institutionalization of his personal philosophy – “Xi Jinping thought in the new era” – have had a profound impact on Chinese politics and society that arguably were not anticipated and have certainly distinguished him from his predecessors going back to Mao. Armed with the powers and standing that he enjoys, Xi could conceivably push drastic reforms especially in the post-pandemic environment. He could well do something highly unpredictable. Indeed, in the US, there are concerns that Xi, having taken a strong approach to cracking down on political freedom in Hong Kong, may be intending to take some kind of strong action on Taiwan.

8. He believes in the CCP and the need to counter the West

Xi truly believes that the CCP will ensure national survival and secure the people’s happiness. His fervor for the party outstrips even those of his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. “The party leads everything”, Xi had written into the party and national constitutions. Absolute leadership by the party has been the biggest feature of the CCP’s leadership in the Xi era.

One more symbolic and substantial feature of Xi’s politics is its emphasis on “Chinese characteristics” (中国特色). Through policies on domestic and foreign affairs, education, and even medicine, Xi has repeatedly emphasized the importance of values such as spirit, resolve, wisdom, culture, sense of civilization, and so on. For example, in tackling the Covid-19, Xi promoted the use of traditional Chinese medicine. He has urged Peking University to strive to become world class but to maintain Chinese characteristics.

The rest of the world should take notice of Xi’s Chinese chauvinism (compared with Trump’s “America First” populism) and his inclination to resist the West, particularly its liberal democratic values and political systems. Xi believes that the Soviet Union collapsed due to actions taken by the US to undermine it. He sees American support for the Hong Kong protesters, the trade friction with Washington, and US moves to put down China’s technological challenge as a concerted effort to contain the rise of China, undermine the CCP’s leadership, and eradicate socialism with Chinese characteristics.

These perceptions are not likely to change with the advent of the Biden administration. “Biden’s views on Xi have totally changed over these years,” the American China expert noted. “Biden will deal with Xi very toughly.” The new US president’s diplomacy and security teams are unlikely to compromise on critical issues such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Xinjiang which China sees as “core interests”. The Trump-Pompeo approach of attacking the CCP is likely to continue. Biden has announced a plan to convene a group of like-minded democracies around the world. He is expected to try to rally allies and partners together to come up with a coordinated China strategy. That may prove difficult, especially after Trump’s unpredictability and rough treatment of Washington’s old friends. The EU’s conclusion of a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China before Biden took office suggests that European countries may not so readily toe the American line on Beijing.

Meanwhile, Xi and his officials will remain highly cautious in their approach to the new US administration, mindful not to undermine Xi’s leadership and foundation of power, or weaken the unity of the CCP. Xi will likely view the “Longer Telegram” as a real challenge from the West against him personally and as a dangerous attempt to promote a schism in the CCP. This will doubtless stoke further Xi’s distrust and frustration with the West and could presage a deterioration in relations with the US and its allies just at the time when there is ample opportunity to dial down the rhetoric and lower the tensions.

Further reading:

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.