Usman Hamid, Director of Amnesty International Indonesia, founder of Public Virtue, and lecturer at the Indonesia Jentera School of Law, in The Jakarta Post (December 20, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Presidential Secretariat Press Bureau)

This year Indonesia witnessed a rollback of human-rights reforms. Marking this regression was President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s security approach to tackling Covid-19, opting for an economic agenda and the imposition of hyper-nationalism, which resulted in a further turn towards authoritarianism and state control of the internet.

Covid-19 exacerbated this through the securitization of all social and political life, enabling security actors to clamp down on political opposition by means of legal instruments, including handling the pandemic. Instead of implementing science-based policies, President Jokowi chose a military-dominated structure that produced a hardline security approach to public-health matters.

In April, the National Police headquarters instructed officers to act against “hoax spreaders” and those who insulted the president and his administration. The police launched criminal investigations into around 100 cases related to the government’s response to the pandemic. The government and the House of Representatives passed the Job Creation Law to strengthen further business interests, while undermining workers’ and environmental rights. The National Police issued another directive intimidating and criminalizing critics of the law, increasing the rise of cyber-authoritarianism.

All of this happened against a backdrop of increasing online intimidation in many forms that included credential theft, spam calls, digital harassment, as well as abusive intrusions into online discussions. Criminalization by the state apparatus under a draconian cyberlaw is not the only instrument of internet control. Media reports have implicated the government in the deployment of an army of pro-regime trolls, trained to debate anti-government forces on the web.

While 2020 will no doubt be remembered as the year Indonesia – and the world – faced an unprecedented health crisis, we should remember it as a year when the country’s human rights crisis deepened, when our civic space for protests and public criticism shrank, and when Indonesia’s leaders abandoned human rights.

Sawada Yasuyuki, Chief Economist, Asian Development Bank (ADB), in The Asahi Shimbun (December 18, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: tokyoaaron02)

While more than 2,000 Japanese deaths are attributable to Covid-19, the pandemic has taken a toll of severe economic, social and emotional impacts on large segments of the population, which may have led to the higher suicide numbers in recent months.

The reasons behind suicides are multi-faceted and complex, but evidence repeatedly points to the deterioration of mental health as one of the critical risk factors in Japan and around the world. The Covid-19 pandemic has induced social isolation, fear, uncertainty, anxiety and economic hardship, causing a lot of mental stress globally, which could lead to a global mental health crisis. What is worse, while physical distancing has proven effective in reducing contagion, it undermines real-world social interactions, networks and bonds among people.

This highlights the importance of promoting “wellness”, which is the pursuit of activities, choices and lifestyles that lead to a state of overall health. Wellness is multidimensional and leads to holistic health, happiness and well-being. It is central to development and is, in fact, one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (goal No. 3).

To keep high levels of wellness even while social distancing, access to digital platforms such as social networking services will be crucial. Digital learning opportunities will also be essential to ensure that students continue to study at home during the pandemic. Governments can play a critical role in mitigating the digital divide – the unequal access to online services – by increasing investment in information and communications infrastructure and making their services affordable and inclusive. Governments can support public infrastructure that promotes overall wellness, including walkways, bicycle lanes, parks, recreation centers and free sporting facilities.

Wellness will not only improve the physical and mental health of Asians but can also act as an engine of growth. It is vital for Asia’s post-pandemic recovery.

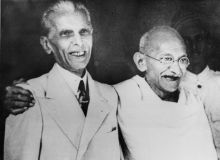

Faisal Devji, Professor of Indian History at the University of Oxford, in The Indian Express (December 27, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes

What would the history of India look like if seen through the lens of caste? Banias changed India’s modern history was the development of the Indian National Congress as a mass organization under Mahatma Gandhi. The Kshatriyas displaced by colonialism had by then been replaced in politics by Brahmin lawyers and administrators. The first Bania to take power from the Brahmins who dominated the party, Gandhi gained for it the support of India’s traders.

If Gandhi’s rise to power signaled the emergence of a new national culture for Hindus, Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s rise accomplished the same for Muslims. The culture of learning and honor that had characterized the League’s Brahmin and Kshatriya elite was replaced by a Bania focus on contractual politics.

Religion has come to define national culture in both India and Pakistan, allowing different castes to identify with each other by excluding minorities. While Hinduism provides a home for many sectarian cultures in India, Islam in Pakistan is exclusive.

While Christians and Hindus are discriminated against and even persecuted in Pakistan, as Muslims and Christians sometimes are in India, they are not seen to represent any serious threat to Islam. This means that Islam comes to dominate politics in such a way as to obscure both caste and religious difference.

If the suspect religious minority in Pakistan is to be found within Islam, non-Muslim groups come to represent not religious but caste difference. Christians and Hindus also serve as repositories for the caste identities of Muslims, who escape their status by displacing it onto them. While caste differences in India are also displaced onto a religious minority, in Pakistan this displacement locates the minority within and caste outside Islam.

Caste really does allow us to see history anew.

Zahid Hussain, journalist and author, in Dawn (December 23, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Gabriele Giuseppini)

Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi has again warned of an Indian plan to launch a “surgical strike” on Pakistan. For a Pakistani leader to describe an Indian plan of blatant military aggression as a “surgical strike” is beyond one’s comprehension. Surely the foreign minister did not realize what the term might convey, but in diplomacy one needs to be extremely careful about the nuances. It is indeed a grave situation and one that needs to be handled more seriously.

Any military incursion into Pakistan would be a risky gamble by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Such reckless action would also be in danger of spiraling out of control and turning into a full-blown military conflagration. The underlying calculation of Modi’s escalation is that India can afford this brinkmanship given the country’s diplomatic clout. But it is hard to believe that any blatant act of aggression will go unnoticed.

A major challenge for Pakistan, however, is how to respond to the Indian bellicosity. There is no doubt that Pakistan’s armed forces are fully capable of effectively countering any Indian military adventurism. But foreign aggression cannot be defeated by military means alone. The country’s major vulnerabilities are its weak economy and perpetual political instability.

There is a need for a broad consensus on key national security issues. Lack of clarity on national security is a failure of our leadership. It is mainly the responsibility of the prime minister to provide leadership. Instead of taking parliament into confidence on the Indian escalation, the political leadership has relied more on media and tweets to inform the nation about the threat. Our diplomatic efforts have also been hampered by the lack of a robust foreign policy. We need a more proactive approach to meeting the serious security challenge while refraining from creating panic.

Sara Soliven De Guzman, Chief Operating Officer, Operation Brotherhood Montessori Center, in her As a Matter of Fact column in The Philippine Star (December 21, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Rudy and Peter Skitterjans/Pixabay)

To many, this will be the saddest Christmas. Covid-19 has disrupted our lives. It has created such a crisis, destroying homes, work and the human spirit. Christmas will not be the same this year. Our homes will be silent, our tables half empty, but we must not let the darkness take over the light that should continue to shine in our hearts. We need to feel that hope and to fight the feeling we have in our hearts. We need to do this not only for ourselves but also for our children.

On the brighter side, we have family to support each other. The simple celebration around the table with prayer and reflection will cleanse our spirits and hopefully make us better. It is during a crisis when our “will” or “might” can be tested. The life that we have now should bring us closer to God.

This will be the first Christmas for millions of families around the world to spend without their loved ones who were taken by the virus. Let us light a candle or two for all those who have gone this year.

The sad part is that some people do not even feel the hardship of the times. They continue to go out and party like there is no tomorrow. These past days have shown us how many of our countrymen continue to ignore social distancing. They have forgotten about Covid-19. Surely after the holidays our Covid-19 cases will spike again. Do not forget we have not even gotten the vaccines yet.

So this is Christmas. Love is the strongest weapon we have in order to survive this pandemic.

Riant Nugroho, Chairman, Institute for Policy Reform, in Jakarta Globe (December 17, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Muchlis Jr/Cabinet Secretariat of the Republic of Indonesia)

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo made a bold decision when he announced that the coronavirus vaccine will be available for free for everybody. He volunteered to be among the first to get inoculated. His remarks make it clear that the government remains committed to saving people, while at the same time encouraging skeptical Indonesians to take the vaccine.

From the perspective of public policy studies, future leaders can take two lessons from Jokowi’s decisions. First, policy leadership is the key to excellent governance. Policy scholars argue that excellent public policies are more effective tools to help achieve one country’s goals than its natural resources and other variables. Still, they are important but not the key determinant. Policy excellence depends on the capability of the top leader in formulating policies, turning them into actions and controlling their implementation across the nation. The main task of the head of government is therefore concerned mainly with policy development and deployment.

Jokowi has never attended public-administration or public-policy schools. However, he has proved himself to be a fast learner during his remarkable journey in public office – from the mayor of Solo to the governor of Jakarta to the president of Southeast Asia’s biggest country. Early in his second term as president, he is already extremely skilled at policy leadership – a subject rarely taught in public-policy schools. Indeed, the second lesson is that policy leadership is the key requirement for any future leader and has to be taught as a core competence in national leadership training institutions.

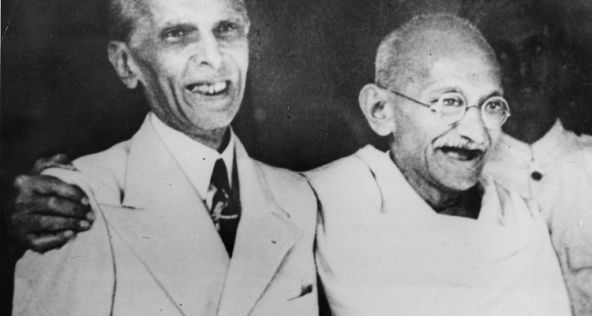

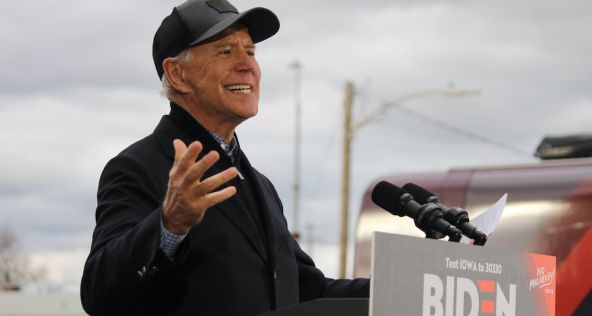

Miyake Kuni, President of the Foreign Policy Institute, Research Director at the Canon Institute for Global Studies, and special adviser to the Cabinet, in The Japan Times (December 11, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Matt Johnson)

The great majority of people in Tokyo and in many other capitals around the world remain ambivalent about a new Joe Biden administration.

The Europeans realize the US’s diplomatic focus has shifted from the West to the East, although they may not wish to admit it. Political leaders in the Middle East and North Africa region are also cognizant of the fact that US attention is shifting from the Middle East to East Asia. Nations in the Indo-Pacific, with the obvious exception of China, will welcome growing US attention to the region. Many, including Japan, hope that Biden will not drastically change Washington’s current positions on China, although his rhetoric may differ from that of Donald Trump.

All in all, the friends and allies of the United States have their own agendas they would prefer to advance irrespective of what a Biden administration may wish to pursue. It is high time for those allies to unite to compete with China – and with Russia and Iran to lesser extents. Fortunately, the Indo-Pacific region has a head start with the creation of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, comprising the US, Australia, India and Japan. European nations have yet to join the diplomatic and military arrangement.

The United States and its allies must resume strategic discussions as they once did before Trump assumed office. The global alliance system is not a zero-sum game. For the Indo-Pacific to prosper, Europe and the Middle East do not need to suffer. To be a truly global community of like-minded nations, all must benefit and assist each other.

It must also be noted that this global alliance system is not aligned against any specific nation. China, Russia and Iran are welcome to participate. To that end, the Biden administration must still promote universal values, including those of liberal democracy, human rights and the rule of law.

Namira Samir, doctoral student at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in The Jakarta Post (December 15, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Alexandra Koch/Pixabay)

The Covid-19 pandemic has required almost all events to go virtual. Information about conferences and seminars has been disseminated through digital posters containing the speakers’ photographs. One cannot close one’s eyes to the male favoritism in Indonesia’s institutions. It is a rarity to find an event with an equal number of men and women. Even those that do include women put them into gender-dictated roles such as chairperson.

Why is this the case?

Indonesia may have fewer problems than other countries with equal pay between genders, but the problem we have is no less systemic than the wage issue. Women need to receive the same acknowledgement for their leadership capacity and their understanding of issues within their field. Both men and women have important things to say, and by putting on a blindfold regarding this matter, we allow the perpetration of gender inequality.

Systemic gender inequality requires the attention of everyone – both men and women, regardless of their occupations or backgrounds. How can one claim that progress has been made when male favoritism in leadership has not been addressed? In promoting women in leadership, developing countries mainly appreciate empowerment in terms of their ability to run their own small and medium-sized enterprises. That matters.

But gender inequality also persists in the formal sector – a sector that upholds the highest standards of giving decent wages and protections to its workers but does not actually have a clear vision when it comes to gender inequality in leadership.

As much as it is the responsibility of policymakers, it is also our duty – that of individuals, men or women – to make a difference, wherever we dedicate our time and knowledge. If each of us passes on the acknowledgement of gender inequality in leadership to our friends, families and colleagues, a revolution will come.

Hong Gi-bin, political economist, in Kyunghyang Shinmun (December 5, 2020)

Summary by Soomi Hong (Photo credit: Cheong Wa Dae, The Republic of Korea)

The year 2020 will be remembered first for the pandemic and second for the widespread distrust and dissatisfaction with governments. The virus has been powerful at physical destruction but also at shattering social unity and paralyzing the global economy. In less than a year since the Covid-19 outbreak, so-called developed countries have broken down on so many levels, and too many lives have been lost in the process.

The UK government has approved a vaccine for distribution to British citizens. Other developed countries will be approving and releasing other versions. But none of the current vaccines have fully completed comprehensive tests on possible side effects, and while some argue that this was necessary to speed up the rollouts, this course of action is no different than that of heavily criticized Russia and China that already started using their own versions of imperfect vaccines on their population.

Understandably, pharmaceutical companies are requesting a blanket exemption from liability for any potential side effects from widespread vaccination. The rush, the irresponsibility of governments and manufacturers, and the potential disastrous side effects have increased the possibility that many will refuse to be inoculated with any vaccine. South Korea has already seen a rise in vaccine resistance following the unexpectedly high death toll from seasonal flu shots. According to a Pew Research Center poll in September, 51 percent of Americans would refuse vaccination.

Vaccines may be the key to save us from Covid-19, but the strategy that governments are pursuing may make this rescue impossible.

Chetan Bhagat, author, in his The Underage Optimist column in The Times of India (December 6, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes

Covid-19 vaccination will be a mammoth exercise, and preparation for this needs to begin now. For India, the magnitude of the task at hand is huge. Having a two-dose vaccine (such as the Moderna version) implies that 2.6 billion doses will need to be given across India. We are talking tens of thousands of trucks (with cold storage facilities) making millions of journeys across the nation around the clock. It also means having healthcare workers vaccinating Indians in every town and city.

This exercise, if not done smoothly, could turn into chaos – something that happens in India often. Instead, we want to show the world that when it comes to the crunch, India knows how to come together.

If we do our preparations right and set our priorities right, we can start in January 2021 and vaccinate a major part of the population by May 2021. We could, therefore, eliminate Covid-19 and be back to normal in terms of economic activity by June next year. If we do not plan or execute properly, we could lose another six to 12 months of economic activity, not to mention a lot more lives.

India can do this if we all work together. Sure, despite all plans, there will be hiccups, as expected in any massive exercise like this. However, we have to remain as one through it all. Non-partisan, non-argumentative, non-left or right. We just need to put our heads down and do the work until all of us are vaccinated. Executing this well will make Indians safe and bring our economy back. Let’s join hands and extend our arms to get the jab we have been waiting for.

Kavi Chongkittavorn, journalist, in Bangkok Post (December 8, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Ron Przysucha/US Department of State)

The new US administration’s perception of Thailand's geostrategic values in the wake of China's rise and the Covid-19 pandemic will determine whether the US's oldest friend in Asia will be a boon or a bane.

First, Thailand has to bring back that image of a rules-based democratic country that respects human rights. If the Biden administration hosts a Summit of Global Democracy next year, Thailand must be included in the list of participants as part of the emerging liberal democracies group.

Second, Thailand is one of the five US allies in the Indo-Pacific region.

Third, Thailand is an important trading partner of the US.

Fourth, Thailand is considered a major regional hub of multinational civil society, especially those with headquarters in the US and Europe.

Fifth, local human rights defenders are fearless when it comes to defending civil rights.

Sixth, of late, the proliferation of social media and bloggers have allowed for the expression of views once considered taboo. Today, all Thai media content providers, which are still lacking in professionalism, report in a way never before seen.

Seventh, Thailand is a good friend of China. Therefore, Thailand can serve as a bridge-builder for the two superpowers, as we have no qualms about being an American ally while being close to China.

Eighth, in the era of the pandemic, Thailand is a great partner for health security. Thanks to more than three decades of US assistance in capacity building and research on contagious diseases, Thailand has developed a world-class healthcare system and capable human resources which have helped mitigate the horrible virus.

All in all, these Thai eight strategic values should help the Biden administration set a clear pathway to deal with Thailand.

Takemi Keizo, member of the House of Councillors of Japan and World Health Organization (WHO) Goodwill Ambassador for universal health coverage, and Achim Steiner, Administrator, United Nations Development Programme, in The Japan Times (December 4, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Prachatai)

Covid-19 has devastated communities, systems and economies. For much of the world, and especially vulnerable populations, these past 12 months have been filled with insecurity and hardship. Driven by the common goal of ending the worst pandemic in a century, there has been unprecedented collaboration between scientists to develop effective vaccines and treatments.

Widespread cooperation around multilateral efforts such as COVAX, the initiative to drive equitable access to successful vaccines, illustrates that many acknowledge the need for solidarity in building a coordinated, global response. Some countries such as Japan have already taken significant steps toward preparing the national systems necessary to provide free vaccinations to all, prioritizing the needs of the vulnerable and underserved. Many low- and middle-income countries, however, where Covid-19 has caused even further strain on health systems, do not have the capacity to act similarly.

A synchronized international effort is needed. The UN secretary-general recently noted that ending the global pandemic will require sustained investment in health systems and a renewed commitment to universal health coverage, calling on countries to guarantee that health care technologies are accessible and affordable to all who need them.

Weak health systems can hinder a pandemic response. Technological advancements are crucial to curbing the spread of Covid-19, but they are not a silver bullet. Health, development and human security will be at great risk if communities do not have timely access to both innovations and strong health systems capable of delivering them equitably. Universal health coverage is crucial for addressing inequality. Investing in stronger health systems and accelerating progress toward universal health coverage through domestic efforts and global cooperation will bridge the gap between the rich and the poor, as well as lead to smoother and more equitable distribution of health technologies, while helping to protect everyone through the pandemic and beyond.

Ambika Satkunanathan, lawyer, human rights advocate and member of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, in Daily Mirror (December 8, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Thomas Timlen)

The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka conducted the first national study on the treatment and conditions of prisoners from February 2018 to January 2020. The findings are very relevant in light of the prisoner unrest and violence that have recently taken place in prisons in the context of the spread of Covid-19.

Prisons are overcrowded to 107 percent of capacity. The study found that prisoners live in severely overcrowded accommodation and even take turns to sleep at night, or sleep in the toilet due to the lack of space. Prison buildings are outdated and dilapidated with crumbling structures and leaking roofs, which pose a constant risk to prisoners’ lives. These structures are highly susceptible to natural disasters, and there are no disaster management protocols in place to deal with emergency situations.

Due to the level of overcrowding, sanitation facilities and water supplies are inadequate to meet the needs of prisoners. At night prisoners are locked in their cells and do not have access to washrooms. Prisoners have to use plastic bags or buckets to relieve themselves and multiple prisoners in a single cell have to use the same bucket. Due to poor hygiene and sanitation, a large number of pests, such as rats and mosquitoes can be a found in prisons. The state of prison healthcare is far below the expected standard of care. Prison hospitals do not receive specialized medicine and equipment. Healthcare is far below the expected standard of care.

Persons from disadvantaged backgrounds are further marginalized by the justice system. Rather than prevention of crime, the prison system pushes persons into a cycle of poverty and marginalization. We need to reimagine the prison system to ensure a safer society.

Fatemeh Halabisaz, entrepreneur and researcher, and Vincent Jerald Ramos, postgraduate student in public policy at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany, in Rappler (November 30, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: International Labour Organization)

In calamities such as the pandemic, the youth are left behind, adversely affected in terms of employment opportunities, education and training, and mental health and wellbeing. Public policies ought to be targeted to help them.

The youth unemployment rate has increased from 12.9 percent in April 2019 to a record-breaking high of 31.6 percent in April 2020. Aside from the immediate disruptions to learning caused by Covid-19, there is also learning inequality. Students from more disadvantaged households find it difficult to continue their education since most of the financial burden from online distance learning falls on the student. An internet subscription is too high a cost for many Filipino households. Add to this the fact that the average internet speed in the Philippines is among the slowest in the region.

Another impact of the pandemic on the youth is a more challenging school-to-work transition. Economic crises tend to cause mass unemployment and create an unhealthy job market, especially for new graduates. Many youths are having to cope with stress and anxiety, which is exacerbated by the pandemic. There are many other confounding effects on the wellbeing of youth such as loneliness, isolation, loss of motivation, and unfortunately for some, possibly even violence and abuse at home.

The government has both the mandate and the ability to pay closer attention to the youth in its post-crisis economic recovery plans, keeping in mind that they are disproportionately affected during recessions. A combination of passive and active labor market interventions may provide immediate relief to the most vulnerable youth and give them the means to enter the job market. An unemployment insurance program could also be an appropriate long-term labor-market policy response.

Huma Yusuf, writer, in Dawn (November 30, 2020)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: DFID)

Arguably Pakistan’s biggest problem is water scarcity. The country faces acute water scarcity by 2025 and will be the most water-stressed country in South Asia within two decades. Almost 30 million Pakistanis have no access to clean water. One would think that the best way to spur discourse on water scarcity would be to focus on basic human rights: the right to access clean water, food and maintain hygiene.

Another approach could be to emphasize that Pakistan’s water crisis is in fact a failure in water management, an example of our governments’ and bureaucracy’s inability to deliver basic services. Studies argue that Pakistan’s water scarcity can be addressed through data gathering, improved efficiency, reduced losses and improved sowing. More and better-coordinated government initiatives and subsidies, such as the drip irrigation scheme in Punjab, are needed. The 2018 National Water Policy needs a revamp, and aggressive implementation.

But the water management argument has not caught the public imagination. The national debate on malnourishment, which affects one-third of Pakistani children, also fails to make the link with water scarcity. Malnourishment is highest in Pakistan’s irrigated districts, where agriculturalists prioritize growing cash crops for export over domestic food security.

If Pakistan is to rally around the need to address water scarcity, it needs a new narrative. Water needs to be reframed not just as a citizen’s basic right but also as a political priority, central to our prosperity. Fisherfolk are campaigning for the Indus River to be granted personhood and associated rights. Many see the idea as too radical. But it indicates the desperation of those most affected by water scarcity. It might be just the new narrative we need to talk about our most pressing problem.

Asia Global Institute

The University of Hong Kong

Room 326-348, Main Building

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

asiaglobalonline@hku.hk

+852 3917 1297

+852 3917 1277

©2025 AsiaGlobal Online Journal

All rights reserved. Terms of Use - Privacy Policy.

Opinions expressed in pieces published by AsiaGlobal Online reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of AsiaGlobal Online or the Asia Global Institute.

The publication of AsiaGlobal Voices summaries does not indicate any endorsement by the Asia Global Institute or AsiaGlobal Online of the opinions expressed in them.

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.