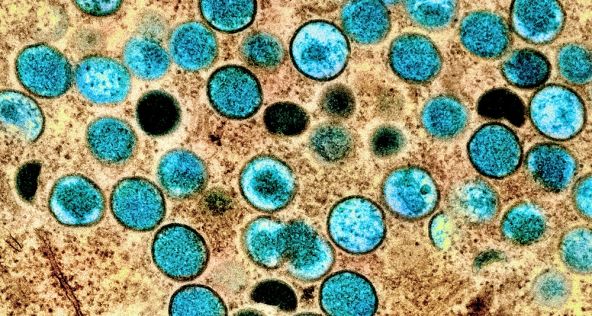

Shyam Saran, Indian foreign secretary from 2004-06 and honorary fellow, Centre for Policy Research, in The Tribune (July 19, 2023)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Xu Qin/Xinhua)

On the sidelines of a conference in Beijing, opportunities for conversation with former and current Chinese officials provided a window to the range of Chinese perceptions about India and the prospects for India-China relations. The Chinese continue to insist that the border issue should be only one component in the full range of relations, that it should not be allowed to define their overall character. This is an implicit rejection of the Indian position that the situation on the border is “abnormal” and this cannot but adversely impact bilateral relations.

Despite several agreements to undertake a joint exercise to clarify the Line of Actual Control (LAC), the Chinese have refused to do so. Not clarifying the LAC enables China to play on supposed ambiguities to encroach upon Indian-held territory. Overall, the standoff at the border is likely to continue and there seems to be no prospect of disengagement of the heavy troop deployment on both sides.

My conversations in Beijing took place soon after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s successful state visit to Washington. Chinese anxiety over progress in the Indo-US relations was palpable. There were concerns that India was becoming part of the US strategy of containing China. One other Chinese complaint was that India had “downgraded” the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) by hosting a brief online summit rather than holding an in-person meeting and that this had been done under US influence.

Overall, one had the impression that China was feeling more unsure of itself and felt that India had proved to be adept and agile in advancing its interests. This may be related to pessimism about China’s economic prospects, even as India seems to have become the new destination for capital and technology flow. Does this presage a shift in the stance towards India?

Rahul Shivshankar, editor-in-chief, Times Now, in Beyond The Headline in The Times of India (June 19, 2023)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Adam Schultz/The White House)

The excitement in the run-up to the India-US summit is proving a little too much to bear for some commentators. The UK newspaper Economist‘s analysis for one oozes condescension, dismissing the summit between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and US President Joe Biden as a bacchanalia of transactionalism between America and a client state – no questions asked, no strings attached. But the facts suggest that the conclusions drawn by the Economist suffer from a profound lack of balance and substance.

First, the Economist has not referenced any proof to back its claims that India’s democracy has measurably slid. The other most egregious assumption the Economist has made is that Western democracies are perfect and are the one-size-fits-all standard to which the rest of us must aspire. Only neo-colonialists sworn to cultural exceptionalism would today dare to exalt a strictly Western sense of democracy and stand in judgement of another model.

The most outrageous insinuation in the piece is that the Indo-American relationship is based on “fewer principles” than the two nations “care to admit”. This is a jaundiced unidimensional view of the bilateral relationship. Delhi and DC are “natural allies” united by a shared liberal political and moral philosophy that flows in India’s case from its ancient pluralistic dharmic tradition and in America’s case from the high ideals of the Enlightenment.

This enviable core of exalted civilizational values commits the two nations to pursue altruistic foreign policy objectives for the greater good of humanity – indeed, even when in pursuit of their individual and sometimes diverging interests. There are many examples of Indo-American collaboration driven by the elevated objective of bolstering a global rules-based order. Is it the Economist’s case that the influential Quad alliance lacks a moral core and is based on “fewer principles” than the grouping would “care to admit”?

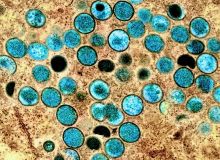

Giridhara R Babu, professor and head of life-course epidemiology at the Public Health Foundation of India, in The India Express (July 27, 2022)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: NIAID)

A rare contagious rash illness known as monkeypox has recently been found in more than 50 countries. The good news is that most infected people will have minor illnesses and recover on their own. It is a self-limiting disease with symptoms lasting two to four weeks and a case fatality rate of 3-6 per cent. When symptoms appear, it is critical to isolate the infected from other people and pets, cover their lesions, and contact the nearest healthcare provider. It is also critical to avoid close physical contact with others. Most people will recover completely.

Despite mild illness and a low transmission rate, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared monkeypox, a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) to contain the disease. It is unclear whether the Covid-19 pandemic is exacerbating the current monkeypox outbreaks.

Never before in history have three infectious diseases (poliomyelitis, Covid-19 and monkeypox) been declared a PHEIC at the same time. Regrettably, this will not be the last time. There will almost certainly be more of these occurrences in the future. The world is yet to recognize emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases as a genuine threat. The immediate priority is to strengthen the surveillance infrastructure, including hiring public health professionals and field workers who can participate in outbreak detection and response during many future PHEICs. Mechanisms for initiating contact tracing, quarantining exposed people, and isolating infected people should be institutionalized. Without prioritizing the strengthening of public health, the threat of new and re-emerging infectious diseases, as well as the enormous social and economic challenges that accompany them, is real and grave.

Chetan Bhagat, author and columnist, in The Times of India (May 6, 2022)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: ILO)

Step outside to a public area in any Indian city – it is almost like Covid never happened. Sure, a few people still wear face masks. For the most part, Indians are out at work or at play. Covid of course is not fully gone. Cases are rising, even though deaths are not. But for now, we are back in business.

Our neighbor China, on the other hand, faces a very different situation. Covid cases there are rising dramatically, and severe lockdowns are back. China effectively kept Covid in check for the last two years but the zero-Covid policy eventually did not work. This has led to a worsening of a problem the world was already suffering – supply-chain issues. Chinese lockdowns have meant workers cannot reach factories, which means the world does not get goods.

The problem is real. And with every problem comes an opportunity. India can be the hero and savior. The solution to global supply-chain issues is India. The current Chinese supply-chain issues are a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for India to shine and present itself as an alternative, diversified manufacturing hub. The opportunity is now, for a limited time only.

India must act now to attract investments, when procurement managers worldwide are frustrated, wondering where to get the shipload of sneakers or engine parts they needed last week. What are we doing to ensure that every company in the world feels it must have a manufacturing setup in India? China has its manufacturing strengths and will remain a powerhouse. However, the global manufacturing pie is so big that India deserves and can get a bigger slice of it. It is time to tell the world that India is open and ready for business. It is time for Indian manufacturing to be a hero and save the world.

Vikram S Mehta, Chairman, Brookings India, and Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution, in The Indian Express (April 4, 2022)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: President of Russia)

Discussion of the genesis of the Ukraine crisis and the extenuating circumstances behind what is an egregious breach of the territorial integrity of a sovereign independent nation has limited value. What is now required are conversations on how to prevent a further escalation of this conflict. India should play a role in driving such conversations. Its decision to abstain from the UN resolutions condemning Russia should give it negotiating heft with Putin; also, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is on friendly terms with him; and as the forthcoming chair of the G20 in 2023, India can claim standing.

Putin has failed to achieve his objectives. He has not succeeded in overrunning Ukraine, in changing the regime in Kyiv, or in securing a Russian sphere of influence. In the face of such a massive setback, what will Putin do next? Will he look for a face-saving way out of the corner? Or might he compound his original sin by escalating the conflict?

The conundrum is how to get him to look at the world through a different lens – how to get him to accept “defeat” without having to concede he has been defeated. There are no simple answers. A good start would be to set out what should not be done. Putin must not be squeezed into a corner. US President Joe Biden’s saying that Putin must not be allowed to stay in power was injudicious. So too were the comments that countries that buy Russian crude oil will find themselves on the “wrong side of history”. The effort now should be to create avenues for a face-saving backdown. India has the credibility and international clout and PM Modi has a personal equation with Putin. These should be leveraged to end this humanitarian tragedy.

Sanjaya Baru, commentator and media advisor to the prime minister of India from 2004 to 2008, in The Times of India (February 15, 2022)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Embassy of India, Ukraine)

India’s decision to refrain from commenting on the Ukraine issue at the Quad foreign ministers’ meeting in Australia should come as no surprise. It is in keeping with the stance it adopted at the United Nations Security Council when it abstained on a vote on the issue and advised all parties to find a solution. This is an adequate and appropriate stand for India to take.

The sudden rise in tensions between the United States and its transatlantic allies, on the one hand, and the recharged China-Russia alliance, on the other, has spawned many columns in the media on India’s neutral stance. Many enthusiastic advocates of closer India-US relations have been suggesting that the Russia-China alliance and the East-West confrontation are reducing diplomatic space for India and that we will have to move even closer to the US. Some international relations scholars have argued that India cannot hold on to this neutral stand for long and will have to take sides.

This view is blind both to Indian history and strategic thinking. Successive governments in India, from Jawaharlal Nehru’s to Narendra Modi’s, have repeatedly asserted India’s right to adopt an independent stand based on its national interests, without aligning itself with any particular military bloc unless this was necessitated by national interest.

India’s independent voice in international affairs is a manifestation of her national self-image and no political leader, however favorably disposed to one bloc or another, can go against this grain of Indian nationalism. There is no denying that the US-India relationship is the most consequential relationship for India. Yet, India has no reason to favor the return to a “unipolar” world in which the US vanquishes Russia and China and reasserts its dominance over Europe and Asia. Rather, a multipolar balance of power system is a better option.

Anushka Jain, Associate Counsel at the Internet Freedom Foundation; Likhita, researcher and adviser at Amnesty International; and Matt Mahmoudi, artificial intelligence and big data researcher at Amnesty International, in The Indian Express (November 24, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Srinivas Kodali @digitaldutta on Twitter)

You desperately need to get to the pharmacy to stock up on essentials. As you walk there, almost every street you pass has cameras installed, watching closely as they attempt to identify your face and track your movements. You cross the street, only to be intercepted by police officers who demand that you remove your face mask. You ask why, but no one responds. Then, without explanation, you are lined up and an officer captures your face on a tablet.

This might sound like a scene from a film set in a dystopian world. In fact, this is an emerging reality for the people of Hyderabad, which stands on the brink of becoming a total surveillance city. According to police, more than 600,000 cameras have already been deployed in the city.

Facial recognition technology identifies the distinct features of a person’s face to create a biometric map, which an algorithm then matches to possible individuals. The system searches across databases of millions of images, scraped without knowledge or consent, and often fails.

Yet, many police units in India today continue to acquire and deploy this dangerous and invasive technology. In India, these technological infringements on our human rights are particularly dire. The absence of any legal framework to govern data protection, especially in the context of personal biometric data, means that we are blindly turning our public spaces into sites of technological experimentation, where human rights are sidelined for profit and control.

The proposed Personal Data Protection Bill has been stuck for years in Parliament. Meanwhile, police forces and intelligence agencies have accelerated their unchecked personal data collection. Under the guise of the protection of women and children, huge amounts of public money are being spent on these technologies with no evidence of their effectiveness, further squandering precious public funds.

Aaran Patel, master’s candidate in public policy at Harvard University, and Siddarth Shrikanth, master’s candidate in public administration and business administration, Harvard and Stanford Universities, in The Indian Express (November 5, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Government of India)

After weeks of tough talk, few expected India to lead from the front on the opening day of the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow. And yet it did. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement – a series of ambitious short-term climate targets, and a pledge to hit net-zero emissions by 2070 – was a welcome surprise.

The announcement cements India’s important position in the climate fight. Despite being responsible for a relatively small share of historical emissions, India is now the world’s third-biggest emitter, behind only China and the US. With one-sixth of humanity and millions yet to be lifted from poverty, what India does on climate will inevitably shape the world’s trajectory.

Net-zero by 2070 may seem a long way off. But the near-term targets that underpin the headline figure matter far more. None of this will be easy, but the goals point to a quiet revolution in India’s climate ambitions. India’s sheer vulnerability to climate change may have played a part.

To meet the challenge at hand, we see three guiding principles that could help bring this week’s bold pledges to life.

First, India must combine emissions reductions with climate adaptation, embedding environmental justice for people and nature. Second, corporate India has a vital role to play in complementing government policy. Third, to deliver decarbonization and development, India will need data and democratic deliberation. Building state capacity can help the country move from reactive decision-making to proactive planning and execution. But India will also require the analytical horsepower to craft and implement evidence-based policies.

COP26 represents a bold step, but the devil is in the details. Following through on these commitments with transparent, credible action would allow India to demonstrate genuine climate leadership for the rest of the developing world, and secure a better, greener future for its citizens.

Anil K Antony, tech entrepreneur, in Hindustan Times (October 4, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: @narendramodi on Twitter)

A key focus of discussion at both the Quad Summit and the India-US bilateral meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Joe Biden was tech collaboration. While the two leaders agreed to revive a bilateral mechanism for accelerating high-tech commerce, Quad discussions had better defined outcomes. These included an agreement on tech principles and standards and an understanding among the participating countries (Japan and Australia were the others) to build on the work of a critical and emerging technology working group, first conceived at the Quad’s virtual summit in March.

The group is meant to facilitate technology standards development, and identify collaborations on critical and emerging technologies, including biotechnology, semiconductors and future communication technology. A key objective is the creation of resilient technology supply chains. Both the bilateral and Quad meetings focused on low-emissions technology solutions to tackle the climate crisis, as well as cybersecurity.

These are positive developments for India. Disruptive changes in China, however, make the realization of these goals challenging. China’s clampdown on tech companies has been restricted only to the consumer sector, even as state support to hard and manufacturing sectors including 5G/6G, semiconductors, batteries, avionics and space tech has accelerated. This suggests a state-supervised redirection of the tech sector into emerging strategically vital areas to optimize long-term geopolitical and geo-economic gains.

The Quad’s success in high-tech cooperation depends on the ability of the four nations to draw on each other’s strengths and identify opportunities for collaboration. They would also have to work with utmost urgency if they are to keep up with the singularly focused, state-guided competition from China. Falling behind in these strategic emerging technologies, the drivers of the digitally driven economies of our future, will be debilitating for democracies.

Jug Suraiya, columnist, in The Times of India (September 9, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes

As it celebrates its 75th birthday, India looks over its shoulder to get a glimpse of the road taken, and the one not taken. At the time of independence, there were two visionaries to guide the infant nation as it took its first steps on the path of freedom. One was Jawaharlal Nehru, and the other was Mohandas Gandhi.

They had very different personalities and two very different ideas of India. Nehru sought to imbue his country with a scientific temper, a nation whose temples were factories and dams. Gandhi envisaged a village India in which each rural community was a republic unto itself, bound together by the centripetal motion of the spinning wheel.

As prime minister, Nehru had political authority, Gandhi moral suasion. Nehru’s idea of a centralized, urbanized India which gave priority to higher learning as embodied by our Indian Institutes of Technology prevailed at the expense of primary education and grassroots development which would have released the country from the bonds of illiteracy and rural backwardness.

What if the two Indias could somehow have merged? The household of my early childhood was a microcosm which reflected these two ideas. My father was cast in the Nehruvian mold of vigorous discipline and modernism. He never wore Western clothes but had trained himself to speak perfect English; he was a vocal advocate of family planning, far ahead of his time. My mother came from village India and brought with her a lifetime habit of frugality, an affinity with the downtrodden, and an impish irreverence towards pomposity. So you could say I had the best of two Indias. And yet I have regret. For what? That the pupil didn’t have it in him to learn all that he might have from his two mentors.

Ameya Pratap Singh, postgraduate student in area studies at Oxford University and managing editor of Statecraft, an independent daily on global affairs, in The Indian Express (September 1, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Ministry of External Affairs of India)

Should the Indian government provide diplomatic recognition to the Taliban government in Afghanistan? Or should it refuse to do so on grounds of its violent overthrow of the previous Afghan government and the unreserved use of terrorism?

One line of thought is that the Taliban is in control and so recognition must logically flow from that. Consideration of values should not cloud New Delhi’s judgement. India has significant interests at stake such as cross-border terrorism and the drug trade that may be harmed by delayed recognition or non-recognition. Refusing to recognize the Taliban may strengthen the hand of its regional rivals – Pakistan and China – leading intensification of national security threats on its northern frontier.

India adopted this line of reasoning in 1949 with communist China and failed. The Jawaharlal Nehru government felt compelled to provide early recognition to the communists despite close ties with the previous Kuomintang government during the interwar period.

Did early recognition change anything in communist China’s policy? No. Communist China continued to be suspicious of India’s intentions in Tibet and the bourgeois nature of its regime and elites. Moreover, India’s early recognition gave Mao Zedong confidence in his plans to annex Tibet through force in 1950. Goodwill proved to be an ineffective tool of deterrence. The lesson is clear: In the absence of compelling shared interests, building mere goodwill through early recognition provides no returns. Does India have any such compelling shared interests with the Taliban?

With its rhetorical efforts to appear “moderate”, the Taliban has not demonstrated sincerity, but rather a reluctant acceptance that legitimacy on the global stage is a social good that cannot be achieved through force. New Delhi must engage the Taliban but in a manner that uses their need for recognition to draw concrete concessions in areas of key interest.

Suyash Desai, research associate with the China Studies Programme at Takshashila Institution, in The Times of India (August 2, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Sarthak Bikram Panta)

Under the Chinese Central Military Commission Chairman Xi Jinping, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has undertaken military reforms intended to make it a world-class force by 2049. Xi has not defined what a world-class force means. But an informed guess is that it would mean being on a par with the US, UK, French, Russian and Indian armed forces.

Although China’s primary strategic direction is reunification with Taiwan and to prepare for the US contingency during reunification, India and other Indo-Pacific countries are also affected by the PLA’s force modernization. India needs to be cautious of at least four changes:

First, China has built dual-use infrastructure in Tibet to prepare for possible offensive and defensive operations on the border. The PLA is much more capable of forcefully changing the status quo on the border with India. With force modernization and improved connectivity, its ability to convert these standoffs into a protracted conflict has increased.

Second, the PLA is shifting from “near seas defense” to “near seas defense and far seas protection” – meaning protect its interests in the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific Ocean.

Third, China created the PLA Strategic Support Force to increase synergies between its space, cyber and electromagnetic spectrums. This force is responsible for China’s information warfare and electronic countermeasures, cyberattack and defense, and psychological warfare missions.

Finally, China elevated its Second Artillery Corps to the PLA Rocket Force in 2015. This force’s missile systems and rapidly developing space and counter-space capabilities have become critical components of China’s emerging power projection capabilities.

China’s investment in military tech, big data, drone swarms, and other disruptive offensive technologies, its military linkages with Pakistan and the ongoing building of border villages should concern India. These developments have strategic and tactical implications for India’s border dispute with China.

Vijay Keshav Gokhale, foreign secretary of India from 2018 to 2020 and Indian ambassador to China from 2016 to 2017, in The Indian Express (July 19, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: CompleteCommunicationsSwe/Pixabay)

Two high priests of the Chinese foreign policy community, Yan Xuetong and Wang Jisi, have written recent pieces in Foreign Affairs. Their task is to interpret for the outside world what China’s leader Xi Jinping means when he says that “the Chinese people have stood up and the era of suffering bullying has gone, never to return.”

Wang and Yan start by acknowledging that recent changes in US policy mean that relations are unlikely to grow any less tense or competitive. Wang holds America responsible for this adversarial environment. China, according to both, is not to blame in any way, and is simply responding to American provocation.

Both scholars wish to persuade readers (and nations) that unbridled competition can only end one way – badly for America. America is plagued by political dysfunction, socio-economic inequality, ethnic and racial divisions, and economic stagnation. Wang says that Washington must accept that “CPC enjoys immense popularity among the Chinese people; its grip on power is unshakeable.”

Their main message to the Americans is to give up on pressuring China to change its political system as this will be futile, and to return to accommodating the Chinese Communist Party as a legitimate global player. The Chinese message to the rest is to bend to China’s inevitable hegemony.

From India’s perspective, three points might deserve attention. First, the statement that there is a paradigm shift in post-Covid Chinese foreign policy. Second, Yan’s forthright statement that Beijing views America’s so-called “issue-based coalitions” (he presumably includes the Quad, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue that includes Australia, India, Japan and the US) as the most serious external threat to its political security and the biggest obstacle to national rejuvenation. Finally, that China is still offering accommodation if Washington just respects Beijing’s internal order and acknowledges China’s regional dominance.

Ram Madhav, Member of National Executive, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu nationalist volunteer organization, and Member, Board of Governors, India Foundation, in India Today (June 4, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes

Big Tech companies including social media giants have grown big and powerful. With size grew their indifference and intransigence, too. Governments are increasingly finding it untenable. Countries like China, Russia and North Korea used their authoritarian regimes to take a hard-line against the tech giants. Several European countries have taken steps to limit the power of these Big Tech companies and protect the privacy of their citizens. Having experienced the unprecedented power of these companies including the audacity to ban the Twitter handle of the president of the country, the US has initiated hearings to look into the possible power abuse committed by Google, Facebook and Amazon.

The Government of India's response can be described as mild and moderate. Twitter should understand this from the fact that instead of dismissing its self-righteous statement accusing the Indian police of "use of intimidation tactics" and a "potential threat to freedom of expression for the people we serve", the IT Ministry thought it necessary to issue a lengthy three-page rebuttal.

We are living in a technology-intensive world. The 21st Century world has moved on from multipolarity to “heteropolarity”. A heteropolitan world is one in which international power is no longer limited to national governments. We are passing through a transition into the heteropolar world. There will be debates over actions of the governments. Tech giants controlling social media platforms stubbornly resist any regulatory efforts.

It is important to build a national consensus over the need for a rational regulation that would not affect free speech but helps protect the privacy and dignity of the individuals. Big Tech companies such as Google, Facebook and Twitter cannot continue to resist these moves claiming self-regulation.

Tavleen Singh, columnist, in The Indian Express (June 6, 2021)

Summary by Alejandro Reyes (Photo credit: Government of India)

It is time that Prime Minister Narendra Modi realized that when his ministers tell barefaced lies, they reduce his personal credibility. The home minister was not seen or heard during the worst days of Covid-19’s catastrophic second wave. He surfaced to declare that we “controlled the second wave in a very short time” and that India has “set a record in the world for fastest vaccination”. Does he know that out of 100 Indians only 15 are vaccinated, compared to 88 in the United States and 96 in the United Kingdom?

When it comes to shameless lies, the master is the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh. He says his state is now a “Covid-safe zone”. Has he noticed the number of people dying in villages of fever and breathlessness without ever being tested for Covid-19? Has he noticed that his officials conceal Covid-19 deaths by handing people death certificates that simply state that they died of pneumonia or a heart attack?

The most tragic irony of all is that senior ministers in the Government of India seem now to believe their own lies. So, they appear routinely on television to declare that it is state governments who are to blame for the grim shortage of vaccines.

India is facing a health crisis bigger than any we have seen in more than a century and the only way to move forward is by rebuilding rural health facilities at supersonic speed. The prime minister needs the help of every chief minister to do this. When it comes to procuring vaccines, though, it is solely his job and he needs to do this with ultimate transparency. The one thing we do not need are for his most trusted lieutenants to be trying to erase the truth. It cannot be erased.

Asia Global Institute

The University of Hong Kong

Room 326-348, Main Building

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

asiaglobalonline@hku.hk

+852 3917 1297

+852 3917 1277

©2025 AsiaGlobal Online Journal

All rights reserved. Terms of Use - Privacy Policy.

Opinions expressed in pieces published by AsiaGlobal Online reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of AsiaGlobal Online or the Asia Global Institute.

The publication of AsiaGlobal Voices summaries does not indicate any endorsement by the Asia Global Institute or AsiaGlobal Online of the opinions expressed in them.

Check out here for more research and analysis from Asian perspectives.